My back pages, basement edition.

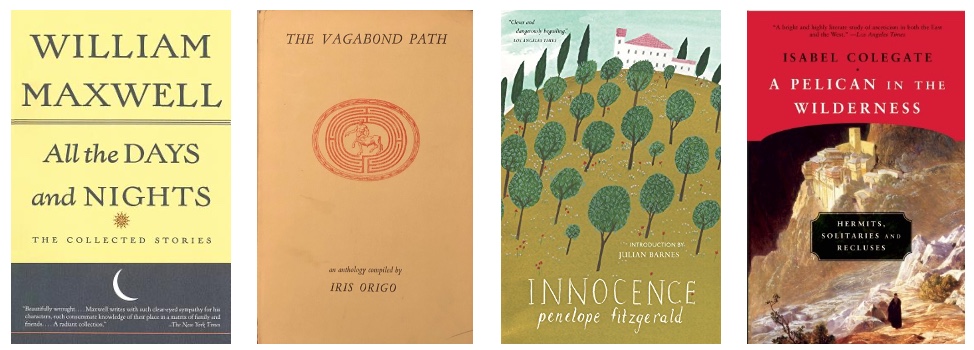

I didn’t expect to be spending so much time in my basement this spring. Displaced from my usual working space upstairs by another family member during our time of surreally pleasant and preternaturally anxious lockdown, I set up a desk (read: cleared off the flotsam and jetsam that the tides of busy life had asked up on it over the past few years) in a warren of bookcases we’d created to house the overflow from the shelves and piles in the living room, library, and bedrooms on the floors above. Although the lighting isn’t optimal for reading and writing, otherwise the ambience is conducive to contemplation, especially since I am surrounded by once familiar books, hundreds of volumes I haven’t attended to with any concentration in recent, and not so recent, memory, but many that, at one point or another, embodied a present interest, meaning, or aspiration: William Maxwell’s short fiction, collected in All the Days and Nights; Iris Origo’s commonplace anthology, The Vagabond Path; Christopher Alexander’s The Timeless Way of Building (more on this marvelous book later in this newsletter); the poems of Anna Akhmatova, the Russian poet who, from 1912 until her death in 1966, created a body of work filled with the biggest virtues—beauty, strength, wisdom, love, sympathy, honesty, courage, loyalty, imagination—while being subjected to the terrors of war and the censure of a brutal government; Robert Coles’s The Spiritual Life of Children, ”an investigation of the ways in which children sift and sort spiritual matters,” that I remember being absolutely engrossing, both in the author’s description of his own intellectual struggle to see, through the dark glasses of science and psychoanalysis, children’s turning toward a spiritual light, and in the webs of words his young subjects weave in explaining their soulful yearnings; Of Time, Passion, and Knowledge by J. T. Fraser, founder of the International Society for the Study of Time, who, I’d learned in a letter from the author that I received after I’d written about his book in A Common Reader, had been a regular customer in my father’s grocery store (“Julius!” my father exclaimed when I’d mentioned the letter. “Nice guy. He liked broccoli. I didn’t know he wrote books.”)

And more: Innocence, Penelope Fitzgerald’s Florentine comedy of manners and family eccentricity; A Prosody Handbook by Karl Shapiro and Robert Beum, the signature “E. H. Cap” inscribed on its title page to indicate an ownership that would pass to me when, sometime after high school, that former teacher allowed a few of us to cull, in pursuit of whatever literary agendas then possessed us, the overstuffed bookshelves in the walkup apartment on West 16th Street, a few steps off 5th Avenue, he was trying to declutter; a signed first edition of Harold Brodkey’s Stories in an Almost Classical Mode, procured for me by an older friend who redirected his life into bookselling about the same time I did; right next to that, don’t ask me why, but in a juxtaposition that the man who gave me the Brodkey would appreciate, Saint Augustine’s City of God. And across the room, Leonard Cottrell’s The Bull of Minos, about the romance of archaeology and unearthing of the remote civilizations that matured into classical Greece. A few spines down the shelf from that, Other People’s Letters, a memoir by Mina Curtiss, translator of Proust’s correspondence, calls to mind the occasion on which I found it, in the dusty labyrinth of the Isaac Mendoza Book Company on Ann Street in lower Manhattan, opened in 1894 and closed in 1990, when our firstborn, Emma, was an infant, a little younger than her son, Charlie, our first grandchild, is now. I remember how old Emma was because of something I wrote at the time—a crown of sonnets, in fact; I was still ambitious in those days—addressed to a friend who’d frequented the bookshop with me. Here’s the first of the seven sonnets the crown comprises;

Over a shoulder, through the humming cloud,

A newspaper focuses my attention

Upon a quiet headline with its mention

Of City’s Oldest Bookstore, Shutting Down.

Imagining a map, I scour the town

But the damned store eludes my apprehension —

Aloft in our Florida-bound suspension

I wish my fellow passenger would read aloud.

No such luck. The baby squirms as I crane

My neck, hoping to catch a clearer word

From the faint gray column of the Times’s prose.

Then letters squint louder to make it plain

And at once I’m wondering if you’ve heard:

Mendoza’s bookshop is about to close.

I could go on for a long time happily cherry-picking and caressing in sentences volumes on display before me, but I’ll bring this indulgent reverie to an end, at least for now, with two brief excerpts from an elegant hardcover I’ve pulled from the shelf just below Mina Curtiss’s memoir. Its title is A Pelican in the Wilderness: Hermits, Solitaries, and Recluses, and its author is Isabel Colegate, a writer better known for her novels, particularly The Shooting Party. The first quotation from Colegate’s book is one I’ll throw far out into the future for Charlie to catch when he’s ready to make his way out into the world on his own two feet, from this moment in the troubled year of 2020 when we eagerly await his first steps:

One can carry one’s solitude with one, as many experienced hermits who have contact with the outside world know very well, and as most poets I would suppose know too, but in the modern Western world solitude is undervalued, and the need for it forgotten. To wish to be alone is thought odd, a sign of failure or neurosis; but it is in solitude that the self meets itself, or, if you like, its God, and from there that it goes out to join the communal dance. No amount of group therapy, study of interpersonal relationships, self-improvement exercises, personal training in the gym, can assuage the loneliness of those who cannot bear to be alone.

The second I set down for me, in acknowledgement of the thin but uninterrupted thread that runs through years, marked by a trail of books that, from this sanctum in my basement, I salute:

What one might call the hermit tendency constitutes a thin but uninterrupted thread through history, a pull of the tide towards some other moon, a nostalgia for paradise or a hope of heaven. Whether for a poet or a misanthrope, a mystic or a seeker for a moment’s silence, there has always been a need for a hermitage.

As I sit here in the early morning quiet, occupying a seat assigned by circumstance in this den of my past selves, it strikes me that volumes, when one reaches a certain age, are anchors rather than vessels for voyages: they hold us in whatever harbor we’ve managed to make our way to, securing, if we’ve been lucky in our journeying, our still buoyant spirits.