On the trail of the OED.

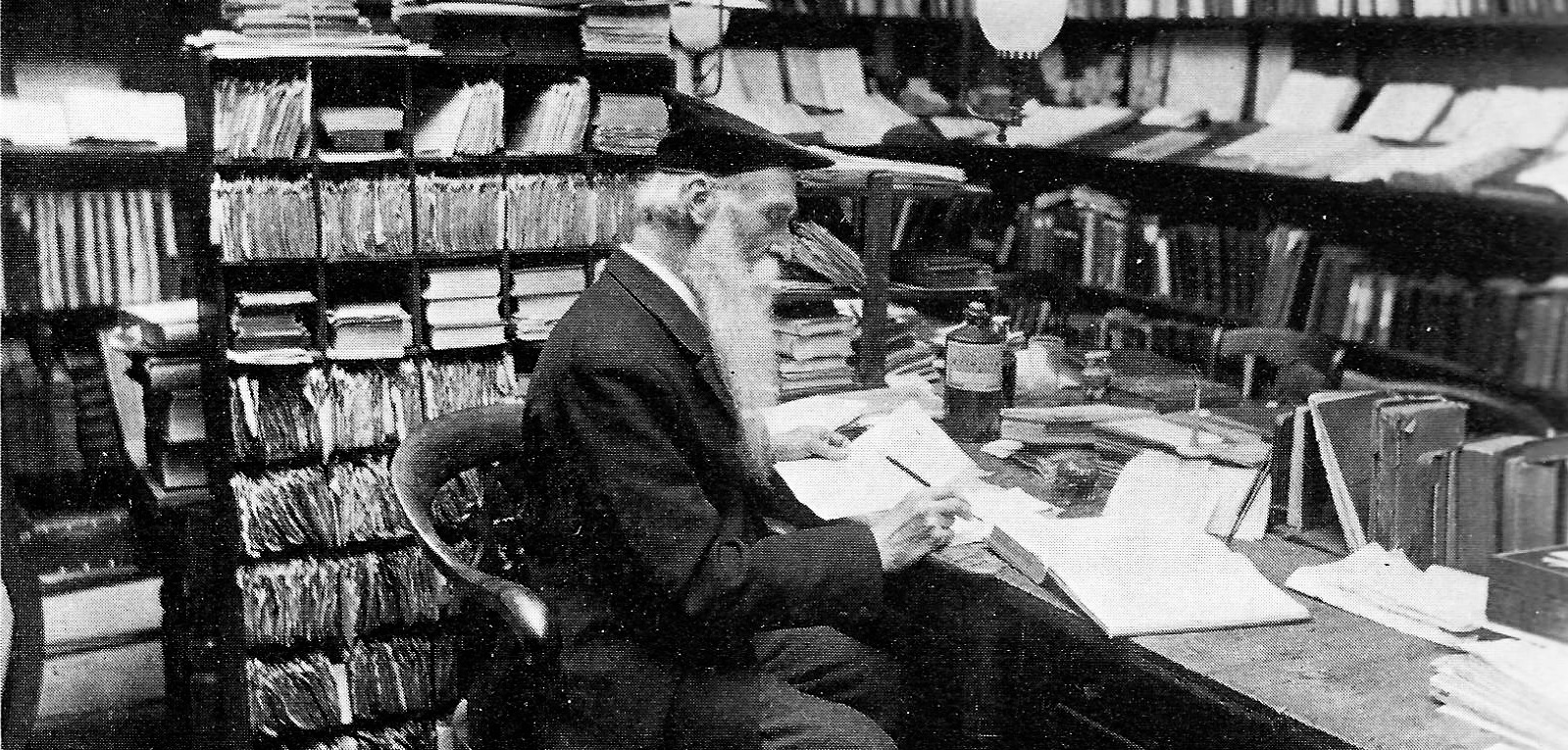

One book my eye alighted on as I worked in the basement last week, when I lifted my eye from my laptop and looked to the left, was Caught in the Web of Words, K. M. Elisabeth Murray’s biography of her grandfather, James A. H. Murray, founding editor and guiding light of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). In the photograph reproduced in the header to this post, Murray is shown at work in The Scriptorium, which housed the hundreds and hundreds of thousands of index slips, inscribed with a word and a quotation illustrating its usage, recorded and sent to Oxford by an army of readers from around the globe, albeit primarily in Britain and America. Nearly two million such quotations, excerpted from all manner of books as well as newspapers, magazines, and other documents, found a place in the first edition of the OED, whose final volume was published in 1928, nearly a half-century after James Murray had signed on for what was projected to be a ten-year project (five years into it, as an emblem of their collaborative intensity and insect-like application, the editors had reached ant). While Murray, who died in 1915, did not live to see the end of alphabet, he engineered the machinery that ensured the project’s completion; few scholars have left a grander monument as a literary legacy.

The poet Richard Wilbur once described a particular volume as belonging to the “aristocracy of reference books.” In such a category, the OED is the entire House of Lords. Among the most comprehensive, authoritative dictionaries ever conceived, its subject matter is the vocabulary of English since 1150; its method is historical: each word is traced from its first documented appearance through all its slow drifts and dramatic shifts in meaning. Yes: it was condemned by its own operating principles to be slipping out of date as its type was being set, yet the natural resources it catalogued and described remained on display, in a newly refulgent and useful way, to whatever imagination could mine them and put them to work.

In his own great dictionary of 1755, Samuel Johnson poked fun at his own labors when he defined lexicographer as a “harmless drudge.”To some degree, James Murray fit that description: a largely self-educated boy from a village of Denholm in the Scottish Borders, he nurtured his fascination with languages through stints as schoolmaster and bank clerk, producing in his off hours various small works of philological scholarship. Elisabeth Murray relates the circuitous route by which the man found his moment, telling, in delicious detail (delicious, at least, to book geeks amused by the publishing vagaries that distract—and the commercial imperatives that obstruct—the unfettered application of high-minded editorial attention) how her grandfather and his Victorian associates built the massive edifice of the OED out of all those slips of paper. In its way, the journey which editor-in-chief Murray and his team made from “A” to “Zymurgy” is a grand adventure yarn. Polymathic novelist Anthony Burgess called Caught in the Web of Words, “One of the finest biographies of the twentieth century, just as its subject was one of the finest human beings of the nineteenth. Everybody who speaks English owes Murray an unpayable debt. Everybody even dimly aware of that debt ought to devour, as I have done, this most heartening story of learning, energy, faith, and sheer simple humanity.”

For those of you to whom this nonetheless sounds like reading drudgery, let me recommend Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary, which reveals a surprisingly lurid subplot to the enterprise’s main narrative, focusing on the most assiduous and skilled of the readers who supplied the word slips that filled The Scriptorium, a transplanted American named Dr. William Chester Minor. Dr. Minor’s neatly handwritten contributions—nearly ten thousand in all—were sent to the dictionary’s Oxford offices from the village of Crowthorne, barely fifty miles away. Editor Murray was understandably curious about his prolific collaborator, but it wasn’t until 1896, after some twenty years of corresponding, that the two men met. When they did, an astounding secret came to light: namely, that the erudite Minor was a long-standing inmate at the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. A Yale-educated surgeon who had served in the Civil War, Minor was incarcerated at the mental hospital for a murder he committed while in the grip of the paranoid schizophrenia that blighted fifty of his eighty-five years (he died in Washington, D.C. in 1920). Winchester tells his sad, tormented, remarkable story with reportorial verve.