The allure of dictionaries.

I suspect my antennae were alert to Elisabeth Murray’s book because I’ve been using much of the time reclaimed these past several weeks from commuting, and from both the purposeful and the pointless scurrying allowed by the freedom to go anywhere at any time, to dawdle in dictionaries, weighing words and tracing their nuances for pleasure as well as expressive advantage. Upstairs, in my usual workspace, I have, conveniently arrayed, the full OED, purchased four decades ago, when I combined an Oxford University Press special warehouse offer to bookstores with my employee discount to bring—with a little scrimping—the then $795 price of the set within range of my $125 per week take home pay. Also within reach of my usual desk are Webster’s Third New International; the American Heritage Dictionary; the Oxford American, notable for its especially readable typography; a Merriam-Webster Collegiate; and assorted other language reference works, including a couple of thesauri and several usage books, with pride of place given to the original edition of H. W. Fowler’s A Dictionary of Modern English Usage and Bryan A. Garner’s Modern American Usage (now Garner’s Modern English Usage in its latest release), which, in addition to be invariably helpful, is almost as delightful to read as Fowler—high praise indeed. (While I’m at it, here’s a clip of the estimable Mr. Garner extolling the benefits of stocking one’s mind, and explaining what commonplacing means; it’s well worth watching.) All of these compendiums make for a happy anchorage in the Sargasso Sea of words I sail back and forth upon.

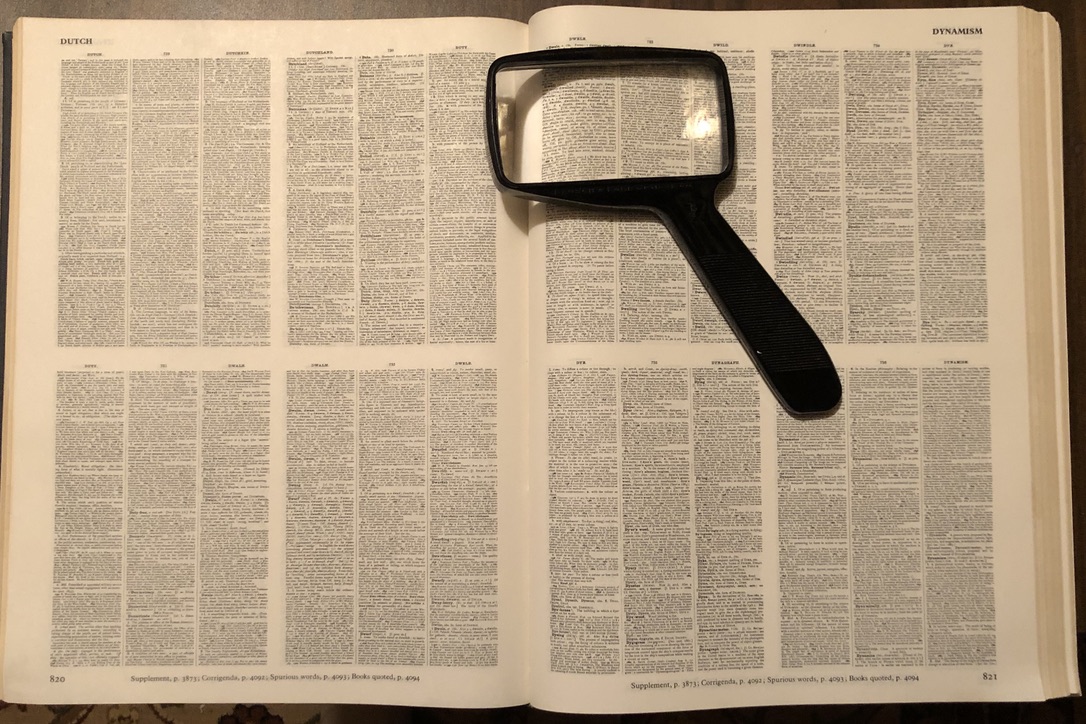

Back downstairs in the basement, where I am working now, I’ve dusted off the Compact Edition of the OED that I used to have in my office back in Common Reader days; not an abridgment, this two-volume version is a direct photo reduction of the complete dictionary, with four of the original pages arranged on each page of the compact volumes. The catch is that you need a magnifying glass to read the text (a fine one comes in a small drawer at the top of the boxed set), but this easily becomes a habit, if not a badge of honor: “Wordhound at Work!”

“I have always been greedy for words,” writes Edmund Wilson at the start of “My Fifty Years with Dictionaries and Grammars,” his long 1963 essay on his sojourns in the linguistic lands of Greek, Hebrew, Russian, and Hungarian (it’s collected in the volume The Bit Between My Teeth). “I can never get enough of them.” He could have been speaking for me. But except for an early infatuation with Latin (see A Classical Education), I’ve never ventured outside English, and am still enraptured by sounding its words to discover what I mean to say along paths of sense, cadence, and surprise. Josh Billings once said, “Words are often seen hunting for an idea, but ideas are never seen hunting for words.” For me, I’m afraid, it’s often the other way round. The dictionaries I collect are props I lean on to liberate my thoughts. Writing sentences, to steal a phrase recklessly from Beckett’s Molloy, I am “restored to myself, free—I don’t know what that means but it’s the word I mean to use.”