Common Prayer

Bookshelf autobiography, via an old catalogue.

I closed a recent post with a question posed by the philosopher Simone Weil. Happily, she’d also provided an answer. I didn’t reveal that Weil’s words were top of mind because I’d come upon them while flipping through an old copy of A Common Reader. As some of you know, that was the name of the book catalogue I cofounded in 1986 and published for two decades. I have a full set of all 300-odd catalogues in archival boxes in the basement, awaiting the verdict of time and decay, which I consult from time to time when I am looking for a particular sentence I think I already wrote a long time ago, or if I feel the need to wander through the verbiage of my halcyon days.

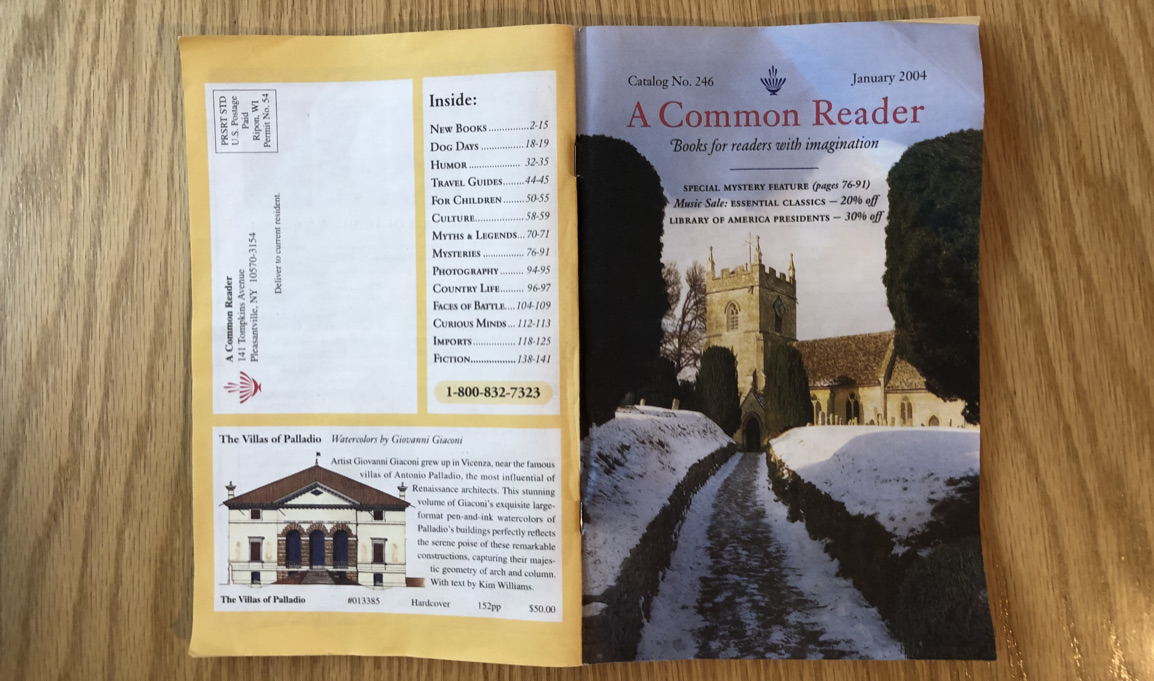

Occasionally I come upon a stray issue of the catalogue when I am cleaning the house or rearranging bookshelves. That’s what happened this time, when a copy of ACR No. 246 (dated January 2004)—newsprint pages wrinkled and torn, yellowed with unturned possibility—slipped from the middle of a pile of books at the bottom of a nightstand. On its cover is a photograph of the snowbanked path to the church of Upper Slaughter, Gloucestershire, from a book called The Most Beautiful Villages of England, with text by James Bentley and photos by Hugh Palmer. Turning the page, I read, in the upper lefthand corner, my customary letter to customers, which opened with the Weil quotation, a formulation I’d forgotten in the intervening years and was happy to rediscover. In the welcome letter, I drew a dotted line from Weil’s profound idea to the more pragmatic purpose of the publication in the reader’s hand, in words I’d echoed in the newsletter I’ve referred to, where they seemed to fit the subject at hand: the perilous state of bookstores in the pandemic-straitened economy.

“What is culture?” the French philosopher Simone Weil once asked. She was not without an answer, and her response has always struck me as particularly apt: “The formation of attention.” To play a role in such formation is, to my mind, the best aspiration of a good bookseller; in this catalogue every month, my colleagues and I attempt to bring your attention to books and recordings that will enhance your private pursuit of culture, or encourage your participation in the broader conversation a shared culture makes possible.

Perhaps A Common Reader performed that function for readers. Every time I begin to doubt it, an email or an encounter with a former customer makes it credible: the strength of some readers’ attachment to that enterprise after all these years always buoys my spirit. What is never in doubt is that A Common Reader, by accidental design, played such a role for me; in the pages of No. 246, for example I can trace something of the formation of my own attention, both contemporary with the publication of that issue and trailing back through the long period of reading and bookselling that preceded it. That’s one of the rewards of a bookish life: the history of our interests, enthusiasms, passing fancies, and concentrations are palpable to us in the shape of volumes arrayed on a shelf of books—or, in my case, in blocks of prose arranged in collections on catalogue pages.

Those catalogue pages also served me in those years as a kind of journal, allowing me to record anecdotes from life I otherwise would certainly have forgotten, since I lacked the patience to keep an actual diary in which I might have filed them away more naturally. Flipping the pages of ACR No. 246, I spy a title, Italian Neighbors by Tim Parks, which supplies a case in point. My original catalogue description of Parks’s book reads like this:

I remember traveling with a friend of mine, who had attended medical school in Italy, to retrieve his transcripts from the university at L’Aquila. At the registrar’s office, he was informed that a verbal request was not enough: a written petition was required. So he wrote out a note, only to be informed that the letter had to employ a formula, exactly duplicating the wording of the sample of florid prose he was then handed. He copied it out and returned to the appropriate desk, to find out that of course he had used the wrong paper; the proper paper—officially watermarked—was available at the post office. Off we trudged, while he regaled me with the tale of the ongoing feud between the woman who manned the post office window and the owner of the bar across the piazza. Once he had tried to mail a post card, but the post office had no supply of the proper stamps. So he walked over to the bar, which sold them. The owner provided him what she insisted was the correct amount of postage, although when he returned to the post office the woman at the window informed him the postage was insufficient. He went back to the bar, whose owner refused to sell him any more stamps because, she claimed, the postal employee was a stupid liar. The two women glared at each other across the square; my friend pocketed his post card and moved on. This is the Italy that Tim Parks celebrates in this funny, affectionate, amusing chronicle of the life he and his wife have lived in the small city of Montecchio, not far from Verona. All the usual charms of Italian culture are here too, of course, and in abundance; but it is Parks’s special attention to the country’s unique marriage of “anarchy without, ceremony within” that make his book such a delight.

Before I continue, for those of you keeping score, the rest of the L’Aquila story is this: after we picked up the watermarked paper, and my friend transcribed the approved language to it, we returned to the university registrar to consummate the deal. My friend was then told to come back in two weeks, when the president of the university—who alone could affix the seal and signature that would unlock the transcripts, as well as the supplicant’s high school and college diplomas, which he had been required to submit when he enrolled (the actual diplomas, mind you, not copies thereof)—would be back from holiday. On the plus side, I suppose, if the process had been efficient, I’d have nothing to remember.

To return to ACR No. 246, a dozen or so pages beyond the Parks entry, I discover a consideration of Richard Watson’s The Philosopher’s Demise: Learning to Speak French, an entertaining and sneakily profound account of the author’s attempt to learn to speak French passably enough to deliver a paper in Paris. Despite the fact that Watson began these studies after three decades as a Descartes scholar, one who could not only read French superbly but translated it professionally, he had a hard time passing muster with the formidable Parisian professors of the Alliance Française. It’s a funny, wise book, and seeing it reminds me of the pleasure I found in striking up a correspondence with the author, with whom I shared a love of black liquorice as well as books. (I wrote more about Watson in the first newsletter of this year.)

Elsewhere in the catalogue I am intrigued to find a forgotten page devoted to what was then piled on my bedside table: a book of poems, The Wild Iris by this year’s Nobel laureate, Louise Glück; Crowded with Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment, a chronicle of the intellectual excitements of 18th-century Edinburgh by James Buchan; Monsieur Proust, an illuminating memoir, by the novelist’s housekeeper, Céleste Albaret, of daily life with an eccentric genius; The Dominion of the Dead, by Robert Pogue Harrison, which, since I described at the time as a “surprising, elegantly imagined meditation on the ways burial of the dead provides the ground in which the seeds of living culture take root,” must not have kept me up at night; and, finally, two sets of reading—the Lyttelton Hart-Davis Letters and Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe mysteries, that have continued to cycle back into my beside rotation in the intervening years.

Flipping through the catalogue’s 152 pages (how did we ever produce these every month?), I am struck by how much of my attention therein is devoted to visual books. On page six, there is an entry devoted to the latest picture book by the remarkable artist Peter Sís, The Tree of Life, a layered portrait of the life and work of Charles Darwin. Like all of Sís’s picture books (including my favorite, The Three Golden Keys, which I’ve included in 1,000 Books), The Tree of Life is an act of imagination in the exact sense, translating complex networks of fact, idea, and emotion into drawings of meticulous detail and ingenuity. It’s powered by a curiosity that transcends the age-delimited audience the descriptor “picture book” might imply.

Below the Sís, there’s a volume devoted to the work of Giorgio Morandi, the mid-twentieth-century Italian painter whose table-top still lifes of nondescript bottles, cups, and vases are singular devotions—there’s no better word—to the mysteries of time, space, and perception. Deeper in the catalogue, I find my attention turned to books about John Singer Sargent and Albrecht Dürer, and another about the art of Johannes Vermeer: “Time itself seems to hang suspended within the frames of Vermeer’s paintings, not only still, but pondering. His exquisite compositions—characteristically domestic scenes of unremarkable event—strike me as three-dimensional in a metaphysical way, as if their careful representation of familiar space took the measure of expectancy itself. rendering the secrets of some sixth sense.”

Paging through old issues of A Common Reader is like a conversation with volumes read and treasured for either passing or permanent reasons; with authors encountered in both books and, sometimes, life; with correspondents who’d recommended their own favorites for inclusion; and, pleasantly and often surprisingly, with my younger self, or, more exactly, with perceptions as they took form and memories as they found expression. Some of these perceptions and memories have become companions enduring enough that I now take them for granted as part of my private culture, the armature of attention I’ve mustered against the anxiety that experience, enigmatic in its increasingly mortal forward motion, engenders ever and always.

On page 98 of ACR No. 246, I find, in a box headlined “The School of Eloquence,” a series of quotations from a sampler of the work of Samuel Johnson. One of them reads: “The chief art of learning, as Locke has observed, is to attempt but little at a time. The wildest excursions of the mind are made by short flights frequently repeated; the most lofty fabrics of science are formed by the continued accumulation of single propositions.” Which makes learning sound a little like prayer, and reminds me that Simone Weil also wrote that “prayer consists of attention.” Are prayer and culture siblings, then, children of the mind and soul who seek meaning and know they always have something to learn, or to praise? And is the real art of learning—pace the assurances of the educational treadmills that train their charges in fungible skills for utilitarian applause and return on investment—a kind of enchantment, an endowment of powers more like senses than like certainties?