“In order to live quietly” in Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend.

Reading E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime a while back, I came upon a passage that crystallized some thoughts about Lenù and Lila, the Neapolitan girls whose friendship is portrayed with fierce fidelity in Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. The sentences from Ragtime appear in a section describing Father’s experience as part of the Peary polar expedition:

Father kept himself under control by writing in his journal. This was a system too, the system of language and conceptualization. It proposed that human beings, by the act of making witness, warranted times and places for their existence other than the time and place they were living through.

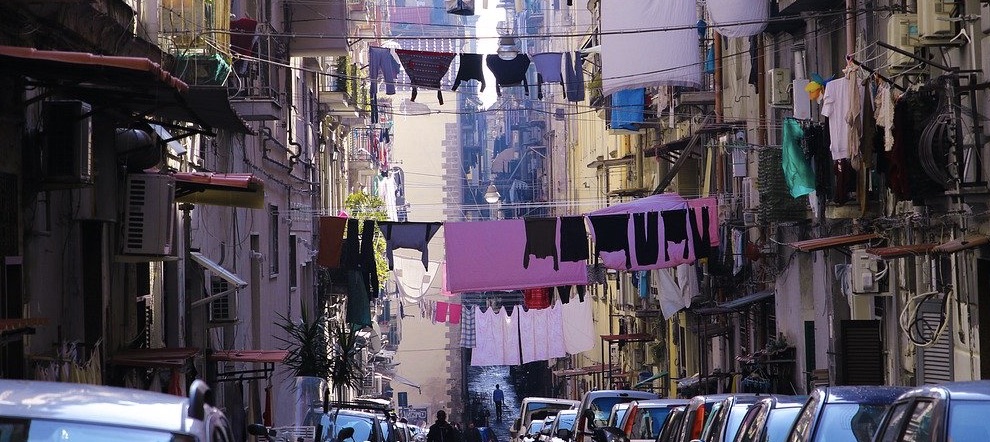

These words returned my attention to what strikes me as a key chapter in the Ferrante novel, in which the scholarly Lenù is led by the no-longer-schooled Lila into thickets of English vocabulary and Greek declensions, as well as into the emotional tangle of Virgil’s story of Dido and Aeneas, the latter girl hungry for the learning and articulation—the systems of language and conceptualization—that the former, given the chance to continue her education, takes somewhat for granted as homework. At the crux of My Brilliant Friend, and central to the rest of Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet, is the power of reading, writing, books: how the narrator (Lenù) alights on them for transport beyond the borders of the girls’ brutally familiar neighborhood, while her brilliant friend (Lila) abandons them for more practical, opportunistic, graspable realities.

Reading acknowledges a past, just as writing invokes a future, and those timelines provide the only path beyond the relentless here-and-now the neighborhood vividly embodies and enacts. Lila realizes this first, and expresses it—exhibiting the brilliance the title endows her with—right after the girls’ discussion of the lovelorn Dido, interrupting Lenù’s catalogue of local boys she insists are infatuated with every move Lila makes.

She said that we didn’t know anything, either as children or now, that we were therefore not in a position to understand anything, that everything in the neighborhood, every stone or piece of wood, everything, anything you could name, was already there before us, but we had grown up without realizing it, without ever even thinking about it. Not just us. Her father pretended that there had been nothing before. Her mother did the same, my mother, my father, even Rino. And yet Stefano’s grocery store before had been the carpenter shop of Alfredo Peluso, Pasquale’s father. And yet Don Achille’s money had been made before. And the Solara’s money as well. She had tested this out on her father and mother. They didn’t know anything, they wouldn’t talk about anything. Not Fascism, not the king. No injustice, no oppression, no exploitation. They hated Don Achille and were afraid of the Solaras. But they overlooked it and went to spend their money both at Don Achille’s son’s and at the Solaras’, and sent us, too. And they voted for the Fascists, for the monarchists, as the Solaras wanted them to. And they thought that what happened before was past and, in order to live quietly, they place a stone on top of it, and so, without knowing it, they continued it, they were immersed in the things of before, and we kept them inside us, too.

What Lila is describing are the thousand and one nights of neighborhood life, the long enchantment of unquestioned—unquestionable—arrangements that one submits to “in order to live quietly,” to pursue love, and laughter, and labor, hoping to lull misfortune into a daze of works and days without engaging the legacies of the past or the freedoms—the invigorating liberty, but also the terrifying, uncertain, unnegotiated independence—of a future, any future across the borders of the known and well-circumscribed world. The fatalistic poverty of the constant present is what Lenù longs to escape, and what Lila, in the wedding that ends My Brilliant Friend, will marry into.

Nostalgia for the old neighborhood, a staple of so many ex-urban lives, but wholly lacking from My Brilliant Friend, is not just a love for the old days, but more truly a longing for days in which old and new had no meaning, for a more or less unruffled now. That now, as the precocious Lila intuits and as Lenù will surely discover as she writes her way into a time to come, is unlettered and, ultimately, unlucky, if not tragic, in its lack of witness to any meaning beyond the pressures imposed by the insistent present tense.

“That conversation about ‘before’,” Lenù tells us, “made a stronger impression than the vague conversations she had drawn me into during the summer.” An impression strong enough, one suspects, to require a lifetime to unravel—or four novels at least.