Sonnets on a bookstore’s demise, 1990.

1

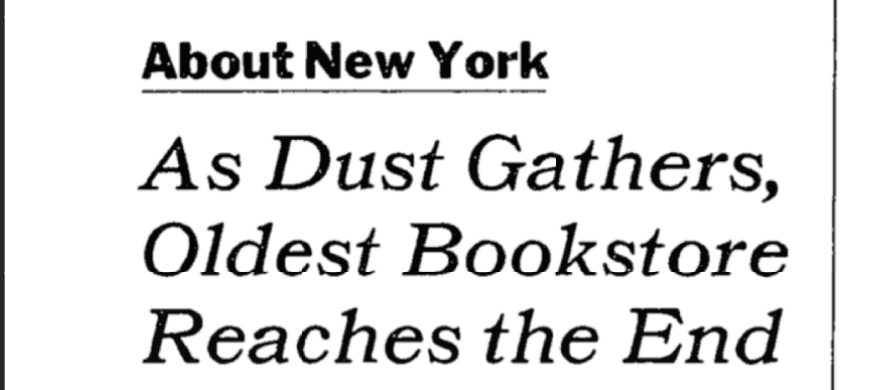

Over a shoulder, through the humming cloud,

A newspaper focuses my attention

Upon a quiet headline with its mention

Of City’s Oldest Bookstore, Shutting Down.

Imagining a map, I scour the town

But the damned store eludes my apprehension —

Aloft in our Florida-bound suspension

I wish my fellow passenger would read aloud.

No such luck. The baby squirms as I crane

My neck, hoping to catch a clearer word

From the faint gray column of the Times’s prose.

Then letters squint louder to make it plain

And at once I’m wondering if you’ve heard:

Mendoza’s bookshop is about to close.

2

“Mendoza’s bookshop is about to close,”

I mutter to my wife, my daughter, too,

But silently I speak volumes to you,

Axel’s Castle, A Mass for the Dead, Rose

Macaulay’s Pleasure of Ruins, all those

Bound enthusiasms we would pursue —

Saroyan, Zukofsky, Marshack, Camus —

Through the cryptic cities a reader knows.

Title by title, we worked miles of shelves,

Unearthing our own dusty alphabet

That spelled out, within dim tottering nooks,

Definitions of our unspoken selves

That will murmur meanings till we forget

The hide and seek of the sibylline books.

3

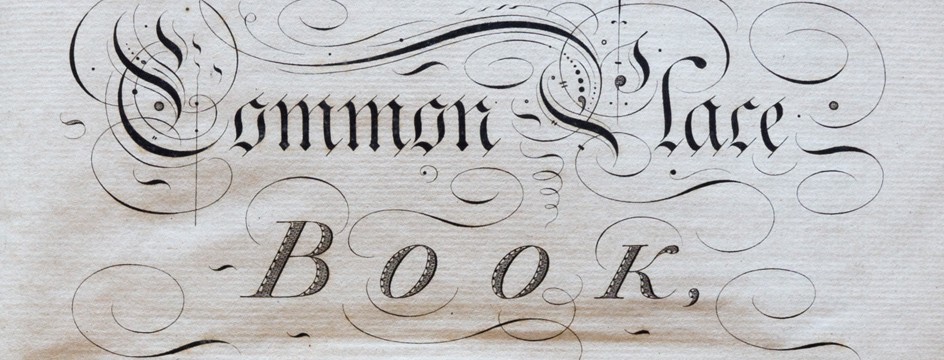

The hide and seek of the sibylline books

Began when old letters enhanced young fate

With prophecies difficult to translate

Into the language that a schoolroom speaks.

Typefaced sirens, disguised as quaint antiques,

Seduced us to their paged estate

Where knowing sentences would conjugate

The moods and tenses of our urgent looks.

Such voices lured us to our first bookcase.

The large, low volumes within childish reach

Led us down alleys alert with spines

To intuition’s spellbound hiding-place:

There unfathomed scripture could start to teach

Before a mind learned to linger between the lines.

4

Before a mind learned to linger between the lines

In love with each sentence’s warp and woof,

Naked intelligence remained aloof

From the deep weavings of a text’s confines.

Worn cloth covers bore talismanic signs

That spoke to starlight through the homebound roof

Which sheltered thought, demanding proof

Of the powers conjured by a book’s designs.

To acolytes serving the will of words

Every book possessed is an oracle:

We swallowed whole bodies of arcane lore

To read the dense entrails of printed birds

Where the guts of life were grammatical,

Encoded in black-and-white metaphor.

5

Encoded in black-and-white metaphor,

Conversation surfaced as best it could;

In Isaac Mendoza’s the talk was good.

The titles’ potential in semaphore

Flashed between us through the word-weary store

While a gas flame fluttered in its brass hood

To warm the close, asphyxiant mood

Poets indulge in, but Muses abhor.

In the bookshop’s mind-webbed, graying air

We sought correlatives to our desire

To find a voice within our intellects,

Shaping a language to be kept with care

On the many pages it might inspire

When we rose from among the analects.

6

When we rose from among the analects

We’d wordlessly study, with restless eyes,

One another’s ration of bound supplies

Exchanging in glances our best respects

Toward the strange interests a friend collects

(In which we’d vaguely recognize

The ghost of our own elusive prize:

The heart’s horn book, with which no eye connects).

A memory ago my parents stored

A box of books for a transient friend

Whose life was running out of space and time;

Up in the attic I honored the hoard

With all the attention a boy could spend

Searching lost libraries to find a rhyme.

7

Searching lost libraries to find a rhyme

The heart dispenses with its own regard,

Trying out postures from the avant-garde

Three parts ridiculous to one sublime.

The books that once scripted our pantomime,

Asleep in their jackets, paper and hard,

Now taunt us, old habits we can’t discard

As we career, head last, into our prime.

I pick up a book and fondle its cover;

At my side, a new hunger nurses, mumming

Her mother through infancy’s shroud.

The plane rushes past the place where thoughts hover,

Yet still I reach back for faint verses coming

Over a shoulder, through the humming cloud.