A round of memories.

“The binaries of the modern moment don’t suit a lot of lived experience,” said Samantha Power. The former United States Ambassador to the United Nations, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning A Problem from Hell: America in the Age of Genocide, was talking to Mitchell Kaplan, proprietor of Books and Books in Miami, on his podcast, The Literary Life. I earmarked Power’s formulation for my commonplace book as soon as I heard it, for it is a succinct, precise diagnosis of the disease that threatens the health of our body politic, to say nothing of the minds that inhabit it. But it’s what she said right afterward that has me kept me thinking about it for the past few weeks.

Power was speaking with Mitchell about her most recent book, a memoir called The Education of an Idealist, which traces her journey from early childhood in Ireland to adolescence in America, high school in Atlanta, college, and careers as war correspondent, activist, and diplomat. While her understanding of the mismatch between our penchant for binary modes of apprehension and the polymorphous realities that ever elude their grasp has clearly been shaped by her professional life, it was the way that, in conversation, she connected it to her childhood that spoke to me most tellingly.

The binaries of the modern moment don’t suit a lot of lived experience. Of course that’s true when you’re dealing with big policy debates, and what to do about ebola or climate change, and the incommensurables of debates in diplomacy or in government, but I’ve thought about it a lot in the context of the pub as well . . .

Why the pub? Because when she was a young girl her father would take her along with him to his favorite haunt and set her up in a special corner where she would read her books and generally entertain herself while he drank with his buddies. It’s a time she clearly treasures in memory, and she conveys it with a sense of warmth and remembered security that belies the evidence of what, as she herself puts it, is on the face of it “Exhibit A of how not to parent.” Things are complicated, she learned early in her education, and it’s a lesson the world would continue to teach her on larger and more historical stages as she grew up.

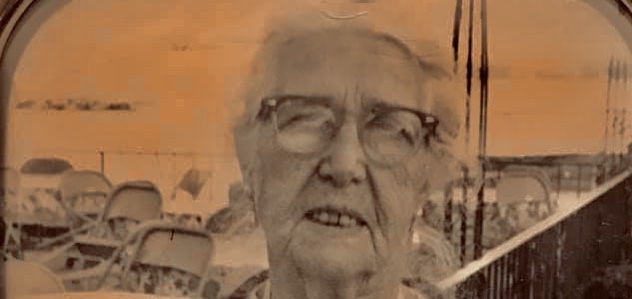

In any case, the child-in-pub scenes Power described were familiar, even friendly, to me. Although my mother never likes to hear me say it this way, I grew up in a bar, the one our family owned during my formative years, and that experience shaped, in many, mostly happy ways, the childhood from which—to employ a handy phrase gleaned from this week’s rereading of Albert Camus’s The First Man—I never recovered. I’ve been thinking about that time a lot lately, recalling it actively in conversation with my father during the restless nights we spend together now while we await, with hope beyond hope, my mother’s return home from her stint in a rehabilitation facility, where the hip she fractured in a fall, a few weeks short of her ninetieth birthday, is slowly mending, and she is gamely beginning to put one foot in front of another again.

The bar is a good subject for us to talk about; the recollections engage us, and my questions about how he came to open it—the partner he ran it with, the physical layout of the place, the lunch menu (my mother cooked), the quantity of beer sold each month—animate his worry with effort and specificity (“every dish on the menu was a dollar”; “325 cases”). The customers who populated it—business people from Reader’s Digest and other local firms at lunch; electricians, plumbers, postmen, laborers from four to six; college students at night and on weekends; elderly card players on Saturday afternoons—were like a big stock company, who took the stage at their appointed hour and carried the show along. There were stars, too, of course, like the state trooper who was the best pistol shot in the nation, and who drank martinis until his ruddy complexion turned beet purple, and the friend for whom our home—an apartment down the street about a half-mile from the bar—was always open, and who sat at our kitchen table every Sunday morning to drink a glass of Harvey’s Bristol Cream as a sort of benediction for the week ahead.

Sometimes, early those Sunday mornings, my sister and I would come into the living room to find a strange young person or two asleep on the floor, my folks having ferried them home at closing time because they needed the support. One beneficiary of such largesse repaid it with a copy of Bringing It All Back Home, a just-released album by Bob Dylan, which was appreciated as a gesture, even if “Gates of Eden” sounded squeaky to ears accustomed to the buoyant swing of “I’ve Got the World on a String.” Others acknowledged gratitude to my parents’ general good will some years later, when they, from a perch at the bar of some local restaurant, would quietly pick up the check for a dinner I was having with a date, leaving the waiter to deliver the surprise; it was hard for me to explain. What I know now is this: at that bar of ours a large, loose family coalesced around a core of generosity big enough to overlook—and when needed embrace—all the frailties and foibles and failures that make lived experience more complicated than any simple scale of judgment can reflect. The bar was closed one day a year: December 25. When we finally moved from an apartment to a house, Christmas day would find 150 or more people traipsing through its front door from morning to night to share—and partake—of the spirits of the season. I’m not exaggerating: I’d sit on the stairs and count them all.

Out of all this, only one photograph I am aware of: a black-and-white snapshot of my father posing behind the bar, festooned with holiday decorations. What’s left are stories, and memories. Even the dates are hazy, but I can bookend them with two vivid recollections. When people ask me the iconic memory question, “Where were you when you learned JFK was shot?”—yes, I am dating myself—I can recall exactly. I was at the bar, having walked there from Saint Thomas Aquinas school; we’d had a half-day of classes because it was the day of the week on which the nuns devoted themselves to religious instruction of our public school contemporaries. When I opened door a pall was on the lunch time crowd, all eyes glued to the small television set above the juke box at the other end of the room. I sat absentmindedly on a stool at the point where the bar turned and made a corner for the cigarette machine. I tried to process what I was hearing. I was eight years old.

Fast-forward a little more than four years to the night of January 20, 1968, when I was in the bar with hundreds of others watching what would be called the college basketball “Game of the Century,” between two undefeated teams, the UCLA Bruins, led by Lew Alcindor (later to become Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), and the University of Houston Cougars, led by Elvin Hayes. The game was televised from the Astrodome, and it is to what we now know as March Madness what the Iliad is to literature; or something like that. The game was close all the way, and I remember my disappointment at Houston’s two-point win; but I remember more vividly the scores of people swirling in the room, heads turned to a maybe slightly larger, but still small, television, while I stood opening one long-neck beer bottle after another on the opener screwed in under the bar, all night long. I’m guessing my father moved more than 325 cases that month.

Six years later, the phone rang in my college dorm room. I was surprised to find Richard Murphy, the Irish poet with whom I was taking a creative writing course, on the other end. “Congratulations,” he said. “For what?” I asked. “That poem you dropped off; the one about the bar.” “Thank you,” I said, “it’s kind of you to call.” “It’s splendid,” he continued. “I hope you don’t mind, but I just read it over the air on the BBC. They asked me to do a half-hour of American poetry. I started with Walt Whitman, and I ended with you.”

I didn’t know what could

be learned in the way men drank

and talked and smoked, my father

wouldn’t be quite so frank

with a little kid, I was

only supposed to learn

in school. He never thought

my mind would later turn

to the smoky scenes he set,

while I sat in some nook

in back and set my own,

eyes glued to another book.

I was speechless on my end of the phone, and Richard invited me to meet him, yes, in the student pub for a whiskey. I’m still tickled by that call: it remains the highlight of my intermittent writing life. But more important to me now is recalling the feeling of the days the poem inscribes, the same feeling Samantha Power evoked in talking of her time in her father’s wayward but welcome orbit. No binary weighing of good or bad can capture it, and even verse is hard-pressed to describe its enduring emotional radiance. What’s left of such childhood quandaries are not documents but memories, past time shaped into tales like those I’ll prompt my father to tell me again tonight when he can’t sleep, the ones I’ve heard on hundreds of occasions but am newly thirsty for as they threaten to fade away, stories that hang over our lives to constellate once lived experience that is as distant from the present moment as the stars.