Looking at the sculpture of Louise Nevelson.

I spent an hour Sunday morning, while the house was quiet, turning the pages of—paying my respects to is probably a better description—a book that looks something looks more like a totem that a volume. Large and nearly square (it’s roughly 12×13 inches), it’s bound in deep black cloth and bears a raised circular emblem of geometric evocation on its cover, where the title is embossed in confident gold: Nevelson’s World.

This bound celebration of the art of the sculptor Louise Nevelson, who died in 1988 at the age of 89, has a place of honor in my home library, on the low shelf for oversized volumes that is directly behind my desk, and where its joined by other books I value inordinately for the inspiration with which they’ve nourished my attention. I set it there when the bookcases were built, more than two decades ago, as an emblem of the artistic, even spiritual, energy it conveys—hoping, I suppose, that Nevelson’s creative example might work some magic through proximity to my writing desk—and it has sat there undisturbed, except for its handling in a fit of dusting several years ago, ever since. Such is the way of the world, to say nothing of the errant habits of once-purposeful appetites.

Until last night, that is, when I discovered it once again, and was once again enthralled. It felt as if I were attending a grand reopening, for the book—authored by Jean Lipman and published, in 1983, by Hudson Hills Press in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art. is one of the most physically stunning I own; its dimensions and weight, the heft of its paper and the elegance of its typography and page layouts, the sumptuousness and care of its capture of the chromatic tones of Nevelson’s wood constructions in black, white, and gold, combine to lure and then embellish one’s alertness the way an historic public space can sharpen our senses with the scents of destiny and endeavor.

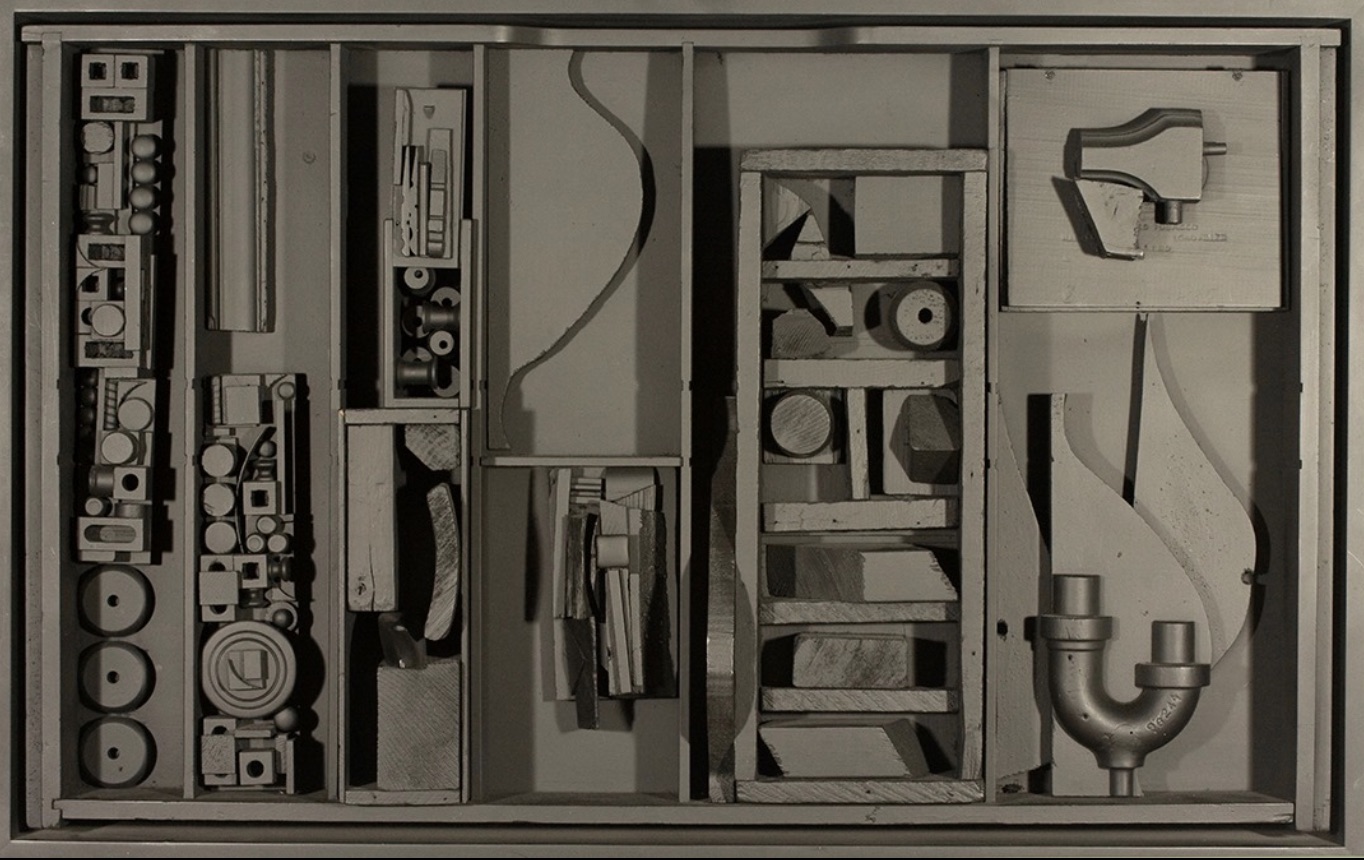

The prompt that led me back to the book was our visit, Saturday afternoon, to the New Britain Museum of American Art in central Connecticut. There, turning a corner out of a room devoted to the sweeping murals of Thomas Hart Benton’s The Arts of Life in America, and a little tipsy from the potent fumes of their invention, I was startled to discover, on a wall in that belonged more to a hallway than gallery, an epitome of Nevelson’s singularity, unassumingly titled Untitled, c. 1985. About three-and-a-half feet wide and two feet tall, with a depth of around inches, it is a box-like structure of found wooden objects—empty thread spools, a clothespin, an isolated link of tongue-and-grove carpentry—painted black, its shapes and shadows transformed into an cohesive entity that exudes the confidences of an altar.

As I pondered Nevelson’s World the morning after, the artist’s voice quoted within it spoke not only to the images arranged on the large pages, but to the memory of the work I’d viewed in New Britain, allowing me to turn over in my mind the perceptions the sculpture, small by Nevelson’s scale, had conjured:

“Anywhere I found wood, I took it home and started working with it. . . . I always wanted to show the world that art is everywhere, except it has to pass through a creative mind.”

“The shadow, you know, is as important as the object. . . . I arrest it and I give it architecture as solid as anything can be.”

“There is in every human being a desire for order. But the artist doesn’t have it ready-made. That is the search.”

Nevelson’s constructions make that search palpable—shares it—with an adamantine ingenuity. Looking at that box on a wall in the New Britain museum, I watched a cabinet of wonders in cross-section, a drawer slid out from the artist’s mind in which antiques are kept and antiquity evoked through uncanny arrangement.

“The most beautiful order of the world,” Heraclitus wrote, “is still a random gathering of things insignificant in themselves.”

“Creation basically,” Louise Nevelson said 2,500 years later, “is that you are searching for a more aware order.”