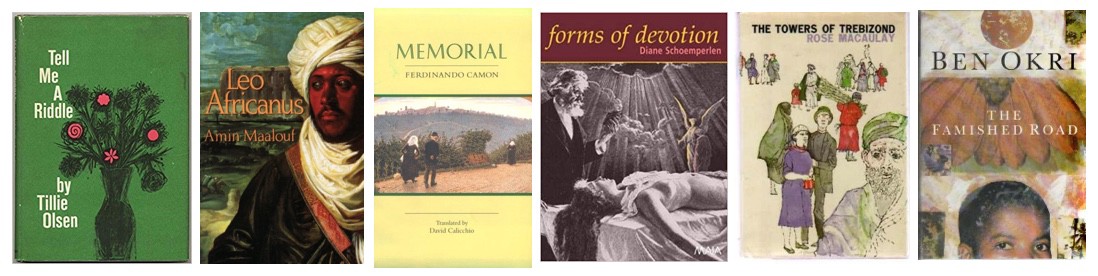

Fiction of far-flung truths and close-to-home consequences: a holiday gift list for off-the-beaten track readers.

Making a gift of a book speaks of our desire for significant conversation, something beyond the daily round of “What’s new?” It’s an emblem of respect, and often special affection, between giver and recipient. By my lights, at least, such gift-giving isn’t always well served by the plethora of “books of the year” or “books everybody’s talking about” that clog media outlets every December; if you share the feeling, you might be interested in this list of eight works of fiction — spanning time, place, and style — that might help you connect meaningfully with the adventurous readers on your list. (For a similar selection of nonfiction titles, see Seven Books Nobody’s Talking About.)

Breaking the Silence of Broken Hearts

Of all the griefs the world can hold, regret can be the most corrosive. The heart’s inventiveness in turning such anguish inward, allowing it to infiltrate conscience as well as consciousness, seems limitless, even though words are seldom a match for its true character. A slim collection of four stories, Tillie Olsen’s Tell Me a Riddle is animated by speech rhythms, its narratives carried along on fits and starts of thoughts and ellipses of memory and emotion. Its genius is the way its prose conveys the abiding argument we have with our own failings and feelings and with the needs, demands, and affections of those closest to us.

The first tale begins like this: “I stand here ironing, and what you asked me moves tormented back and forth with the iron.” (The initial four words provide the story’s title.) What follows reveals a woman’s retrospective remorse for neglect of her firstborn, a daughter of some talent who is now nineteen years of age and into whose personality a teacher or counselor is seeking the mother’s insight. Confronted by the external request — “‘I’m sure you can help me understand her’” — the mother’s interior voice broods upon the shortcomings of her motherhood, deficiencies compelled by personal and economic circumstance and by the sheer exhaustion of making ends meet, and weighs its effect on her daughter’s character. The result is a searing dramatization of life — and love — stunted by class, and labor, and lack of leisure, of fate more earthbound than providential, but nonetheless determining. By the time we reach the end of this quietly shattering tale — only twelve pages since we began — we are staring at a sorrow so deep, we feel dizzy.

The title story, five times as long as “I Stand Here Ironing,” depicts the bickerings of a married couple when the kids are gone and mortality comes to call. The wife and husband have nearly lost their lives in inarticulacy because they’ve lacked the solitude expression requires. In unpacking what this means to them, Olsen (1912–2007) unflinchingly evokes profound emotions in a way that leaves the reader disturbed and humbled by something like the catharsis a tragic drama can deliver. The two stories in the middle of the volume — “Hey, Sailor, What Ship?” and “O Yes” — are marked by a similar empathy and originality. Tell Me a Riddle is an unforgettable book.

A Singular Legacy

A novel that at times seems not very far removed from memoir, The Dead of the House by Hannah Green (1927–1996), is a lyrical evocation of the history of an Ohio family. It is a book of precious strength, as beautifully composed as any American novel written in the second half of the twentieth century.

Covering a period that runs roughly from the 1930s through the 1950s, Green’s novel is narrated by a woman of the author’s age and background. Through the three parts of her tale, in which she progresses from childhood through adolescence into adulthood, Vanessa climbs a family tree as enchanted as a forest, its deep roots entwining the present in all the entanglements of the past. “I thought that if I did go into your woods,” she says as a child to her grandfather, “I would go back into the past and I’d never be able to come out again.” Which is an apt description of what Vanessa does in this book, ruminating on the fate of her family — an old American breed of pioneers and preachers, businessmen and distant women — at the same time as she steps into her self through the familiar crises of coming-of-age: first boyfriend, sibling rivalry, encounter with death. But The Dead of the House is by no means a conventional family saga; it’s more like a book of poems in which meanings are glimpsed rather than grasped, and in which recollection is recast as reverie.

As Vanessa comes into her own present out of the embrace of her family’s past, Green captures our common passage from the almost mythic realm of our childhoods into the realities of our adult lives. Her book is a telling evocation of how we are shaped by our inheritance, bound to our dead by those qualities bestowed on us “by the strange accidents of time, of blood, of love.”

The Life of a 16th-Century Mediterranean Traveler

A transporting historical novel that leads readers across the borders of their parochialism, be it physical, historical, or imaginative, Leo Africanus takes the form of a fictional autobiography of the celebrated geographer, adventurer, and scholar al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzān al-Zayyatī, Born in Moorish Granada in 1488, Hasan fled with his family from Spain to Fez to escape the Inquisition, then journeyed extensively through Africa and the Middle East; captured by Sicilian oceangoing brigands, he was eventually taken to Rome where he was presented to Pope Leo X, who baptized him as Johannes Leo. While in Italy he wrote a trilingual medical dictionary (in Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew) as well as his famous Description of Africa, for which he is remembered as Leo Africanus.

From this remarkable life, the Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf has fashioned a marvelous narrative in which the civilizations of Islam and Christendom engage each other in the experience of a single person. Beginning with an account of the expulsion of Arabs and Jews from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella, the story follows its protagonist’s family to Fez, then traces his peregrinations through cosmopolitan Cairo, across the Sahara to Timbuktu, to the Constantinople of Suleiman and the Rome of Raphael and the High Renaissance. Hasan’s exploits as merchant and diplomat give him, and the reader, an enlightening view of the flux of the sixteenth-century Mediterranean world.

Organized into forty chapters corresponding to the first forty years of Hasan’s life, the book is part history, part travelogue, and, delightfully, part picaresque, replete with pirates and princesses; it places its hero within view of many of the prominent events and personalities of his politically and culturally dynamic time. Satisfying in the many tales it weaves and in the fabled settings it evokes, Leo Africanus is a novel of intellectual discovery and storytelling enchantment.

Requiem for a Way of Life

Despite its brevity — it runs just over one hundred pages — Ferdinando Camon’s Memorial is so extraordinary in its power that, when I first encountered it some years ago, I read it all the way home: I began it waiting for the train from suburban New York to Manhattan, read through the train ride, then continued with one eye as I made my way through Grand Central Terminal to the subway, downtown on the IRT, up the stairs to the street, and on the elevator up to our apartment. I remember to this day standing inside our doorway, keys in hand, until I finished the book. That was thirty years ago; the story, and the experience of my first reading of it, still haunt me.

Written by one of the most notable of Italy’s post-World War II writers, this enchanted autobiographical novel is steeped in the peasant culture of Camon’s native Veneto, an ageless and all-but-vanished way of life the author left behind for the city and the twentieth century. Relating the death of his mother and the building of an altar to her memory by his father, it mixes memory and meditation to evoke his people’s spare, brutal, and profound intimacy with earth, with death, with generation.

“She knew nothing outside her house and those places where she worked,” writes the narrator of his subject, “but those places she knew by heart.” As he describes that house and her labors to nourish her family’s life within it, Camon constructs an altar of words that, like his father’s altar of copper and wood, bears witness to how much such a heart can hold. It’s a small book about a small life; yet the reader who opens it will discover a story moving in its sympathy, dignity, and desire to articulate the deepest human needs.

Fathoming Love’s Deep Currents in Rural Ireland

Like Memorial, The All of It by Jeannette Haien (1921–2008) is a book one can read in a single session. At its start, a priest stands fishing in a salmon stream, pondering the dark secret that the death of a parishioner has revealed, and the astonishing tale the woman who survives the deceased has told him. In Haien’s stunning, rapid, beautiful novel set in a village in the west of Ireland, mortality and morality, sin and sympathy, compromise and commitment are joined in an emotional embrace that is magical, consoling, memorable. It’s hard to say anything more without spoiling the delicate surprise of this spare novel. Poet Mark Strand put it precisely right: “The only book I know in which innocence follows experience. A truly amazing thing.”

A Playful Prayer Book

In her enchanting volume of inventive and unusual stories, Forms of Devotion,Diane Schoemperlen arranges incidents, narratives, and philosophical speculations around wood engravings from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries to create fictional worlds of worship and wonder. The devotions she cleverly examines range from attachments to objects and daily rituals to romantic passions and anatomical attractions. She writes with a detachment that is not ironic but imaginatively analytical: classical reserve meets exuberant originality.

The title story, in which an essay by Emerson seems to have wandered into a story by Italo Calvino, is a lighthearted yet powerful celebration of faithfulness. Other tales explore the resonance of rooms and the innocence of objects, the shifting mysteries of perspective and love (“Love lets you loose in a part of the world where the atmosphere is too rare to sustain human life for long”). One story is constructed as a math word problem: “Train A and Train B are traveling toward the same bridge from opposite directions. . . .”

Another, “Rules of Thumb,” is an alphabet of imperatives for the modern age, beginning with “Avoid the temptations of envy, pride, fast food, and daytime TV talk shows.” Constructing her fictions with a comic, surprising, and deliciously odd formality, Schoemperlen manages to enhance our understanding of an astonishing range of everyday emotion and eternal perception. Her strangely told tales inform one’s attention with a richness not often found in contemporary fiction. Opening this book is like uncovering an unconventional missal that is profoundly amusing and uncannily suggestive.

From High Comedy to High Mass

Tell me you’re not intrigued by a novel that begins, “‘Take my camel, dear,’ said my aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass.” Over a long career (born in 1881, she died in 1958), Rose Macaulay’s grandly individual talent expressed itself in clever comedies of manners (Keeping Up Appearances, 1928), thoughtful forays into idiosyncratic scholarship (Pleasure of Ruins, 1953), and profound inquiries into the elusive nature — and stuttering nurture — of religious faith (tellingly captured in two posthumously published volumes of letters to an Anglican priest in America, Letters to a Friend 1950–1952 and Last Letters to a Friend 1952–1958). All three strands of her literary intelligence are interwoven with élan in her final novel, and her masterpiece, The Towers of Trebizond.

A wonder of eccentricity, absurdity, adventure, wit, learning, and style, the novel is narrated by an Englishwoman named Laurie, who is accompanying her aunt and that freespirited missionary’s consort, the Rev. the Hon. Hugh Chantry-Pigg, on a trek from Istanbul to the fabled Trebizond. Exploiting the appeal of the ancient terrain to modern pilgrims of various stripes (“I wonder who else is rambling about Turkey this spring,” says Aunt Dot. “Seventh-Day Adventists, Billy Grahamites, writers, diggers, photographers, spies, us, and now the B.B.C.”), the first part of The Towers of Trebizond is leavened with comic questions. Will Father Chantry-Pigg be able to establish a High Anglican mission in Turkey? Will Dot emancipate Turkish women by coaxing them to wear hats?

As the book progresses and Laurie is left to her own devices, her grapplings with loves both sacred and profane push the book’s high spirits onto a loftier plane of inquiry. There the tantalizing uncertainties of belief are revealed to be as eerily evocative as the most legend-laden ruin. Must faith’s reach always exceed its grasp? Traveling with Rose Macaulay and her characters, the answer remains in doubt, but the trip, at least, is heavenly.

The Story of a Spirit-Child

“What are you doing here?” one of them would ask.

“Living,” I would reply.

“Living for what?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why don’t you know? Haven’t you seen what lies ahead of you?”

The young boy being interrogated is Azaro, narrator of The Famished Road. What lies ahead of him is a long road of poverty, flood, earthquake, preternatural apparitions, political brutality, separation from his parents, reunion, desperation and mystery, communion with the dead, love and hope — all manner of life in its quotidian and mythical dimensions. That road runs through the center of Ben Okri’s novel, a work of eerie beauty and, despite the book’s supernatural compass, extraordinary fidelity to fundamental human emotions.

Denizen of an impoverished African village, Azaro is a child who has not lost touch with the spirit realm other children abandon at birth. Straddling the temporal and eternal worlds, he chooses a life in time (to the incredulity of his spirit interrogator in the passage quoted above), and his story is animated with both magical wonders and the everyday life of his family and their neighbors. While his parents struggle to keep Azaro among the living, the boy seeks to assume a solid identity in the shifting landscape of vision and actuality he describes.

The family’s intimate milieu is suffused with myth, folktale, and belief, but grotesque political realities (echoing those of the author’s native Nigeria) are never far away, and Azaro’s father — a figure whose exertions as a laborer and heroics as a boxer are rendered with uncanny intensity — is determined to engage them, however futilely. Teeming incidents — his mother’s cagey battles with the landlord, the drunken and dangerous revelry that spills from Madame Koto’s bar, the oppressive presence of factional thugs — are filtered through Azaro’s consciousness and woven by Okri into a mesmerizing narrative both mystifying and curiously true to life. Although the boy’s tale is phantasmagorical, it aches with real human sentiment — imagine García Márquez crossed with Dickens and you’ll approach something of the book’s flavor.

Be warned: If you don’t let the book carry you along, you’ll soon be exhausted by your resistance to its rushing, unfettered imagination. But give in to the current of the author’s musical prose and otherworldly visions and you are in for a transformative reading experience. Okri’s book is bigger than life in just the way that, deep in our hearts, we know our lives are bigger than circumstantial evidence suggests.