Travel Found

In the footsteps of Patrick Leigh Fermor.

For someone who has lived so long on the page, traveling in books, as opposed to real life, is not as impoverished an experience as it might seem on the face of it. Not when there is writing like this to savor:

The sun had gone down but the trees and the first houses of Kampos were still glowing with the sunlight they had been storing up since dawn. It seemed to be shining from inside them with the private, interior radiance of summer in Greece that lasts for about an hour after sundown so that the white walls and the tree trunks and the stones fade into the darkness at last like slowly expiring lamps.

That’s Patrick Leigh Fermor, early in his 1958 book, Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese, describing the waning day in a Greek village with an expressiveness artful enough to illuminate housebound evenings here in Connecticut with warm light from half a world away. The way Fermor builds landscapes on the page, and sends sentences winding through them, is often breathtaking (and sometimes, given his expansive vocabulary and penchant for arcane historical anecdote, arduous). No other writer I know creates so palpable a reality with words, one that seems constructed from stones, from natural formations, from plants and clouds and water. Fermor can summon with sentences a path a reader can follow, treading with care and then abandon as unsure steps gain traction and then are swept along at speed by the rush of sense and sensation the prose conveys. The hunks and colors of the world are caught by words that seem as much a material part of the author’s perception as the rocks and ravines and vistas they describe.

Here he is, again in Mani, describing the Grecian air:

The air in Greece is not merely a negative void between solids; the sea itself, the houses and rocks and trees, on which it presses like a jelly mould, are embedded in it; it is alive and positive and volatile and one is as aware of its contact as if it could have pierced hearts scrawled on it with diamond rings or be grasped in handfuls, tapped for electricity, bottled, used for blasting, set fire to, sliced into sparkling cubes and rhomboids with a pair of shears, be timed with a stop watch, strung with pearls, plucked like a lute string or tolled like a bell, swum in, be set with rungs and climbed like a rope ladder or have saints assumed through it in flaming chariots; as though it could be harangued into faction, or eavesdropped, pounded down with pestle and mortar for cocaine, drunk from a ballet shoe, or spun, woven and worn on solemn feasts; or cut into discs for lenses, minted for currency or blown, with infinite care, into globes.

Actualities that have melted in the heat of time are reconstituted and fixed to his pages by the weight of his words, which are wielded with an exuberance that makes reading a mere couple of pages wholly satisfying—so much so that one can linger on them from one evening to the next, reading them again, and again, the way one might return to the same restaurant in a foreign city night after night, forsaking scores of others, because the flavors and ambience you found there nourished some need you never quite knew you had, and indulging it is sheer delight.

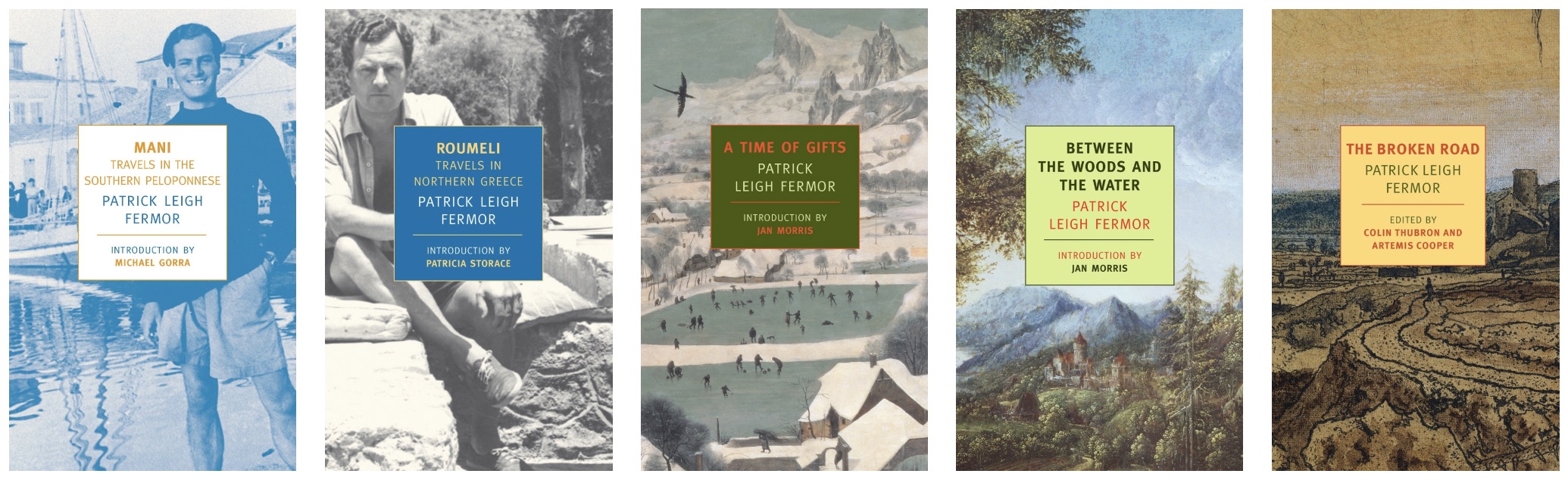

Mani was one of his Fermor’s earlier books. It was followed, in 1966, by Roumeli, a companion volume tracking travels in northern Greece. It wasn’t until 1977, when the author was 62, that his masterpiece began to see the light of day, in the first volume of a prospective trilogy about a journey he took on foot “from the hook of Holland to Constantinople.” That initial installment, A Time of Gifts, was followed nine years later by a second, Between the Woods and the Water (the third segment of the trilogy waspublished posthumously as The Broken Road in 2013, two years after the author’s death; incomplete and not fully polished by Fermor, it is nonetheless a substantial and welcome work). What’s remarkable about these opulent narratives is that the travels they recount with such attention and eloquence were reconstructed from old notebooks and memory more than forty years after the fact, detailing a trek that began in December 1933, when the young Fermor set out from London with a borrowed knapsack and a small weekly allowance (a single British pound). After arriving by boat in Holland, the eighteen-year-old walked from Amsterdam all the way across Central Europe to Constantinople in Turkey. It took him a year and a half, during which he assumed different perspectives: high-spirited young adventurer with a talent for making friends; knowledgeable and insatiably curious student of history and culture; sharply observant eyewitness of the moods and circumstances that were leading Europe inexorably toward World War II.

Together, the two volumes of the trilogy that appeared during Fermor’s lifetime rank among the best autobiographical travelogues in English. The older Fermor’s descriptions of his younger self’s exploits on barges and in beer halls, of his nights passed in barns and in castles, of his encounters with laborers, scholars, and aristocrats—all are suffused with both the innocence of youthful adventure and the sophistication of age’s experience, erudition, and reflection. It is an uncommon combination, layered with strata of time—experiential, remembered, historical—that entwine a rich and cultured consciousness through every paragraph. The very story of the writing of these books, across a stretch of time nearly as long as that which separated the completion of A Time of Gifts from the first steps of Fermor’s walk, speaks to the magic of the writer’s reconstitution of his youth, his sorcerer’s ability to re-member the past in prose that has an almost physical dexterity, casting spells in which words are sense instruments animating sentiments with all they capture. Memory becomes an act of making, rather than a mere cataloguing of what’s past and gone.

Here he is on page one of A Time of Gifts, setting out from London on what would be a pilgrim’s progress across a continent, and many decades:

“A splendid afternoon to set out!” said one of the friends who was seeing me off, peering at the rain and rolling up the window.

The other two agreed. Sheltering under the Curzon Street arch of Shepherd Market, we had found a taxi at last. In Half Moon Street, all collars were up. A thousand glistening umbrellas were tilted over a thousand bowler hats in Piccadilly; the Jermyn Street shops, distorted by streaming water, had become a submarine arcade; and the clubmen of Pall Mall, with china tea and anchovy toast in mind, were scuttling for sanctuary up the steps of their clubs. Blown askew, the Trafalgar Square fountains twirled like mops, and our taxi, delayed by a horde of Charing Cross commuters reeling and stampeding under a cloudburst, crept into The Strand. The vehicle threaded its way through a flux of traffic. We splashed up Ludgate Hill and the dome of St Paul’s sank deeper in its pillared shoulders. The tyres slewed away from the drowning cathedral and a minute later the silhouette of The Monument, descried through veils of rain, seemed so convincingly liquefied out of the perpendicular that the tilting thoroughfare might have been forty fathoms down. The driver, as he swerved wetly into Upper Thames Street, leaned back and said: “Nice weather for young ducks.”

Tonight, I’ll map in the large pages of an atlas Fermor’s peregrination from Picadilly to Prague and beyond, conjuring travels of our own that I can only hope are yet to come.