Time Regained

Reading and remembering in a Soviet prison camp.

The most interesting book I’ve read recently is only about sixty pages long, even though it is about a book fifty times longer than that. It is, in fact, not about reading that longer book, but about remembering it; which couldn’t be more appropriate, given that the work being remembered is Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

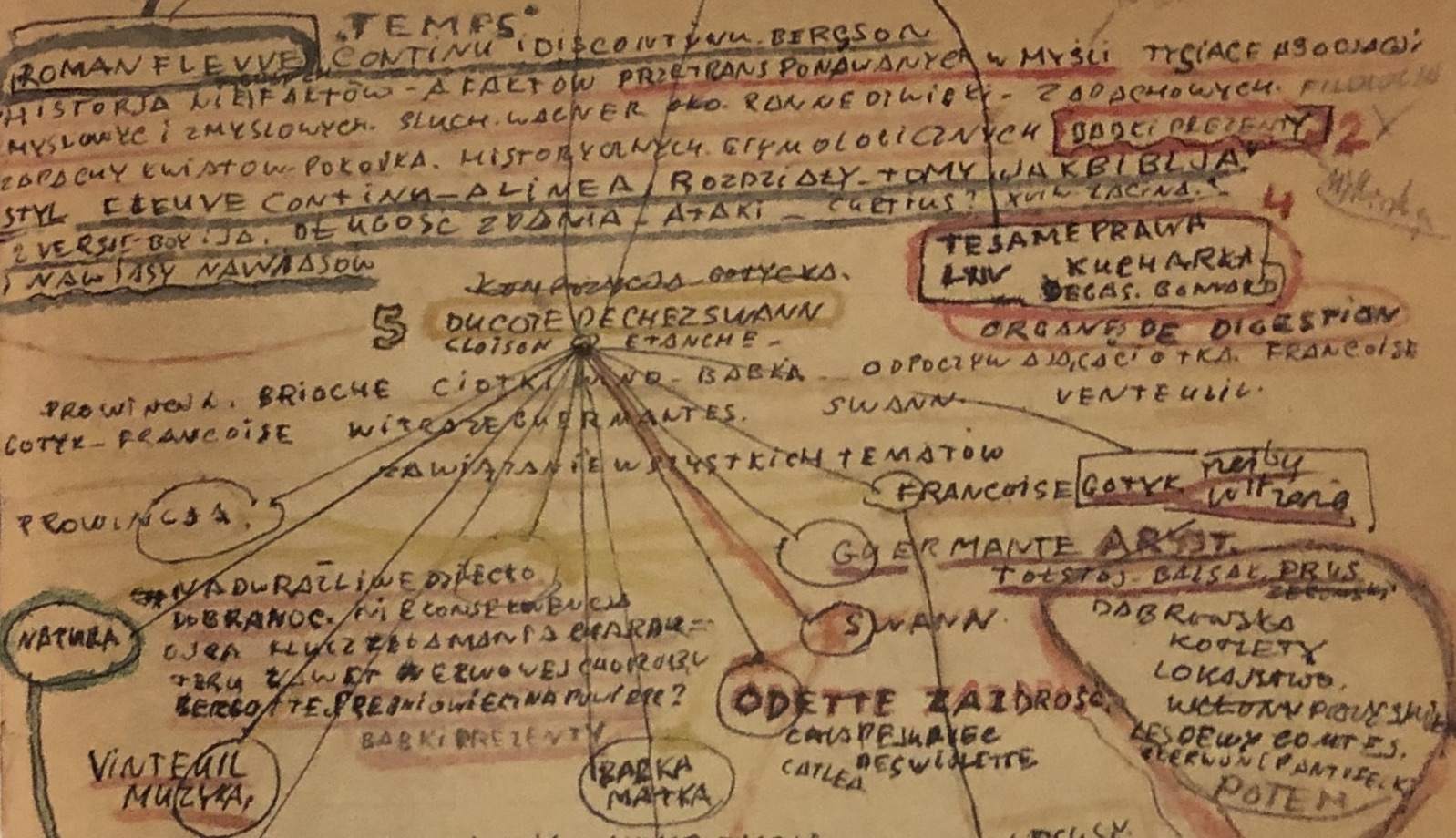

Lost Time: Lectures on Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp, which collects the insights and musings on the French author that one prisoner of war, the Polish painter Jósef Czapski, shared with his fellow inmates to insinuate a liberty of mind into their captive present, is a remarkable meditation on memory and literature and, through these themes, the making of meaning.

In a note later added to the original transcription of his prison camp talks, Czapski writes:

I am quoting Goethe here from memory, perhaps distorting his text. Rozanov [a pre-revolutionary Russian writer and thinker], attacked by critics for imprecise or distorted citations, quipped: “There’s nothing easier than to quote a text precisely, you just have to check the books. It’s far more difficult to assimilate a quotation to the point where it becomes yours and becomes part of you.” If I misquote it’s precisely because of the impossibility of checking in books. Also, I possess neither Rozanov’s glibness nor his entitlement as a writer of genius.

But Rozanov, I think, was onto something, and, as Czapski may have been artfully implying with his note, these lectures on Proust go a long way to validating the value of learning possessed by absorption rather than analysis, apprehension rather than academic precision. The selves we assemble from memory are like a book of quotations, cribbed from experience, education, emotional entanglements, and spiced with the rare and often lonely original thought; in any act of reflection or expression, we put these together—now ordered this way, now that, then scrambled and realigned to meet the pressures of the moment—to keep our identity malleable enough to navigate our days and resourceful enough to make it through our nights.

In his own monograph on Proust (as I learned from Czapski, whose lectures have been translated by Eric Karpeles), Samuel Beckett claimed the author of In Search of Lost Time had a bad memory: “the man with a good memory does not remember anything because he does not forget anything.” Proust’s gift was for remembering, for discovering the past as it unfolded in a space that existed only as he created it from the prompts of the present. If, in its uniformity, as Beckett says, a good memory is “an instrument of reference instead of an instrument of discovery,” the deficiencies of Proust’s, through the demands of his vocation, made a “bad memory” a tool of exploration and even revelation. Like memories, as Proust knew better than anyone, every sentence finds its meaning on the way to it, like a traveler with all senses alert leaving a familiar path without ever quite losing sight of it, finding a perspective on past and future in nearly every footfall of the here and now.