The Making of a Musician

On Jeremy Denk’s memoir.

To write about music is hard. Jeremy Denk does it with as much poise and ingenuity as he performs Bach and Mozart and Brahms, turning the intensity of his study into expression both inviting and absorbing. I’ve enjoyed his prose for years, eagerly seeking it out on his now defunct blog, thinkdenk, and delighting to come upon it in the wild, mostly in book reviews. I still remember an image from a review he wrote ten years ago of Paul Elie’s Reinventing Bach: a score, Denk said, is “at once a book and a book waiting to be written.” Denk’s own acclaimed recording of the Goldberg Variations appeared within a year of his piece on Elie’s book, and it rewards repeated hearing. Before you listen to it, follow this link to the archives of The New Republic to read Denk’s scintillating discussion of the majesty and magic of Bach’s music. (Try this sentence as a teaser: “Bach is all about the beauties of consequences.”)

So it was with happy anticipation that I picked up Denk’s memoir, Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons, published this spring. As the subtitle suggests, the book is structured as a series of lessons, each headed with a playlist of classical compositions that no doubt provide atmospheric accompaniment should you choose to track them down. The text itself—written in supple, conversational, splendid prose—moves between practice and theory. Chapters detailing his coming of age as a budding musician through the adolescent vale of awkwardness (and, let’s face it, there are few beings more awkward, in the familiar American milieu in which Denk was raised, than a prodigy on the school bus, despite the graces his talent was learning to summon at the keyboard) alternate with chapters focused on the fundamental musical capacities—harmony, melody, rhythm—that sound from, and slip through, the fingers of virtuosity. The young Denk’s actual music lessons, with a cast of memorable teachers, taskmasters, and one guru (in the shape, spied through an elegant haze of cigarette smoke, of the Hungarian-born pianist György Sebők), are recalled in all their painstaking hours of suffering and occasional moments of transcendence. While Denk’s mordant humor is a joy throughout the book, it is especially funny when describing the hard work of achieving mastery: “Imagine that you are scrubbing the grout in your bathroom and are told that removing every last particle of mildew will somehow enable you to deliver the Gettysburg Address.”

A pianist’s mastery comes through the hands, and that’s where Denk starts an early chapter on harmony.

I know my hands pretty well. I know these halves better than myself as a whole. My right hand is more agile, more Fred Astaire, willing to throw itself into a flurry of fast notes at a moment’s notice. It has a tendency to try too hard and tire itself out. My left hand is better at solid notes, things that require cushioning, weight, gradation. It can play louder than my right, and more smoothly, but prefers not to move fast; it believes in patience and preparation. You could say that my left hand is older than my right, and wiser, and so much lazier.

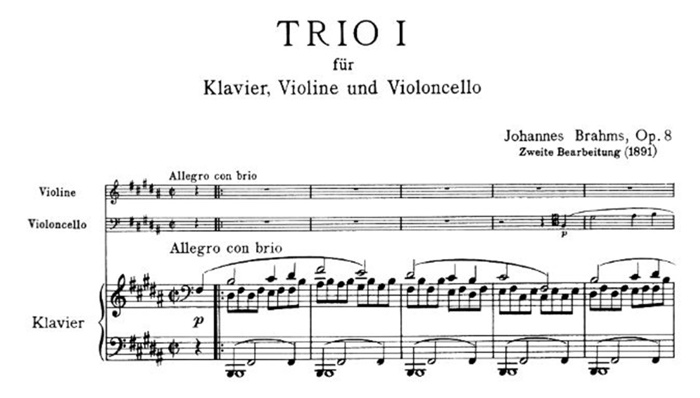

It is this, well, tactile approach to harmony, and then to melody and rhythm, that makes Denk’s book so rewarding. Here he is on the beginning of Brahms’s first Piano Trio, opus 8, in B major.

For the first few notes, it’s just a major scale, nothing memorable. But then Brahms decides to skip one note. This act is crucial and defining: the melody acquires identity and purpose. One skipped note—no big deal. You might say I’m making a mountain out of a molehill: a cutting and fitting indictment, if it weren’t for the fact that melody is the greatest device ever invented for converting molehills into mountains. It’s a stage where details are destined to become momentous. You understand this skipped note is important because Brahms immediately returns to the note he left behind. The gap he’s created must be addressed. I’m trying to describe this in analytical language, so that musicologists won’t roll their eyes at me, but meanwhile it tugs at my heart.

And then there is Denk’s command of musical and cultural context as well:

Melodies belong to specific pieces, but harmonies are shared—across a style, across a culture. They belong less to individuals than to periods of time. Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, between 1770 and 1820 or so, all built off the same basic set of chords, like a starter set of Legos. There are extensions, excursions, extenuations, but basically they work from good old one, four, and five, the fundamental trio. Harmonies are a vehicle, a stage, a backdrop. There are endless famous melodies (“Ode to Joy,” “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” “Like a Virgin”) but it is incredibly, world-historically rare when a harmony is so original that it attains the celebrity of melody.

I could go on quoting this book for a long time. The coming-of-age parts—his trying and, most importantly, enduring relations with his troubled parents; the anxious turmoil of committing to a musical career; the turbulent emotions as he plays hide-and-seek with sexuality—are engaging, and excellent in their way, but as unsatisfying as real life often proves to be; the coming-of-artistry parts, on the other hand, are arresting in the eloquence, and just as good the second time through (I tested this). They make you want to listen better, and teach you to do so, leaving the reader—in my case, at least—feeling the way Denk felt when Sebők sat at a keyboard to instruct him through four bars of Mozart’s Concerto in C Major, K. 415:

Everyone in the room saw the theme’s possibilities at that moment, and also Sebők’s greatest qualities: wit balanced by elegance, refined attention to the smallest distinctions. The result was not a theme but a little machine for the production of happiness, with intricate, interlocking parts. There were no mysteries, in a way, since he’d explained everything; and yet mystery remained.