The Lost Art of Conjuring

On the letters of Julia Child and Avis DeVoto.

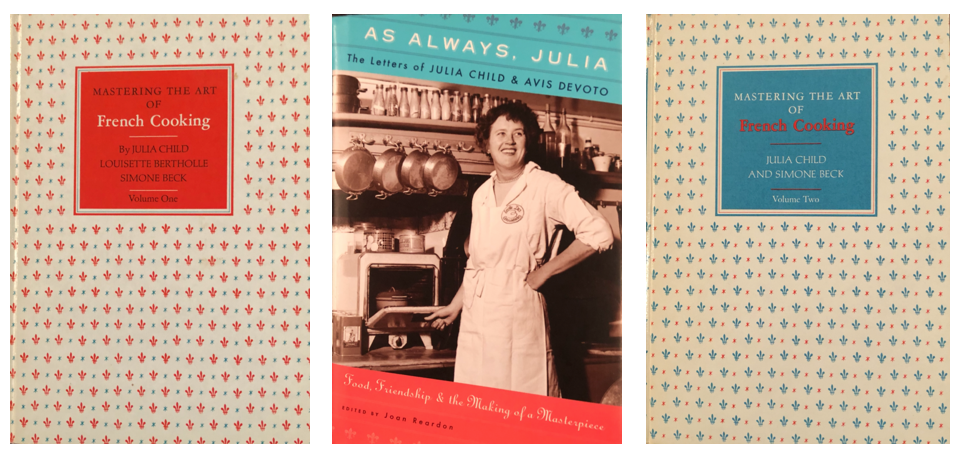

A few weeks back, under The Next 1,000 rubric in Newsletter No. 28, I wrote about As Always, Julia: The Letters of Julia Child and Avis DeVoto. The reader who’d added it to the ever-growing list of titles at the website was my wife, Margot, and her persuasive case for the book led me to conclude the squib in my email by saying, ”If we can find the book around the house, I’m reading this next.”

As it turns out, our original copy was nowhere to be found, having likely made its way into the tottering piles my mother maintains at her house. Fortunately, however, Margot, taking me at my word, had ordered a second copy as soon as she was finished proofreading the newsletter, which is why it was close at hand over the long President’s Day weekend, when I was under the weather but clearheaded enough to enjoy the therapeutic regimen assigned me: sit in bed and read.

I couldn’t have asked for better company in this circumstance than Child and DeVoto. The conversation that unfolds in the long letters between them, Julia writing from France (at the start, at least) and Avis from Cambridge, Mass, where her husband, Bernard, an acclaimed journalist and historian, was an instructor at Harvard, is sheer joy, spiced with culinary insight and gossip social, cultural, and political. As Margot pointed out, it’s suffused with the pleasure of friendship in formation and, ultimately, in full flower.

Assembled, edited, and nicely annotated by Joan Reardon, As Always, Julia was published in 2010 with the apt subtitle, “Food, Friendship and the Making of a Masterpiece.” The correspondence began in 1952, when Child sent Bernard DeVoto a paring knife from Paris. Child had never met DeVoto, but nonetheless was compelled to address his pining for a good carbon steel utensil after she’d read an installment of his Harper’s magazine column, “The Easy Chair,” in which he decried American stainless steel because it couldn’t hold a proper edge.

The thank you note that came to Child in Paris started like this:

Dear Mrs. Child:

I hope you won’t mind hearing from me instead of from my husband. He is trying to clear the decks before leaving on a five weeks trip to the Coast and is swamped with work, though I assure you most appreciative of your delightful letter and the fine little knife. Everything I say you may take as coming straight from him—on the subject of cutlery we are in entire agreement.

She goes on for eight substantial paragraphs—two full, well-packed book pages—about the “cutlery question” and other coincidental matters:

An aside on eating—I am green with envy at your chance to study French cooking. There are two dishes served at Bossu on the Quai Bourbon that I remember in my dreams, and if by any chance you know how to make them I would be forever in your debt if you would let me know.

Julia, of course, takes up this challenge, responding with her recipes for scrambled eggs in the French style and veal with cream and tarragon. The women’s immediate bond, forged by a kitchen knife and fostered by common interests and intelligence, was soon anchored to a project—the masterpiece of Reardon’s subtitle—getting underway: the manuscript that would ultimately become one of the most important American cookbooks of all time, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which Child created in collaboration with two French women, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, but which might never have seen the light of day without the editorial attention and publishing midwifery of Avis DeVoto.

The conception, writing, styling, recipe testing, and various reconfigurings of Mastering the Art of French Cooking—to say nothing of its wayward journey to bookshop shelves, an obstacle course through various hurdles and assorted publishers—provides an intriguing narrative framework to the first, large portion of the correspondence. It’s fascinating in itself and doubly so refracted through the wit and worry of two wise women whose respect and affection for one another was marvelous for this reader to share. I felt like I was making new friends, too.

The slow passage of time across the lengthy letters, the connection forged in sentences and sentiments without a face-to-face meeting for a few years, is epitomized in the real desire each woman expresses for photographs of the other, a circumstance—a kind of suspension of discovery, a tantalizing anticipation that goes beyond the images themselves—that is hard for us to comprehend in our world of infinite pictures and instant communication.

“Now that I know Paul [Child’s husband] is a photographer,” writes Avis in February 1953, nearly a year after their first exchange, “I have a definite request to make. . . . I want Paul to take a photograph of you at the kitchen stove. With or without decorated fish.”

“Yes,” comes Julia’s response, “we’ll send you some photos, but only on the severe condition that you will send us several of the two of you and the two boys. We visualize you as about 5 and ½ feet (you said once that you weighed 112 when your weight dropped, so imagine you would normally be about 125). With dark hair (I don’t know why) . . .”

Three weeks later, Julia again: “And the photographs arrived in the same mail. At last we know! I love the looks of DeVoto, there is a wonderful gaiety and intensity about that face. Now, how do I know whether you look as I pictured you, now that I’ve seen you. You are dark, anyway. That is a wonderfully worldly expression you have on in the group picture, really superb . . . It is the face I always try to wear when I am in New York, with no success.”

And Avis, shortly afterward: “Pictures just arrived. Hooray! I am enchanted with them, and think I will have the big one of you at Cordon Bleu and the extremely handsome one of Paul framed for my Hall of Fame. . . . I am very, very pleased with your looks, so warm and vigorous and handsome. . . . I am rather astonished that you are such a big girl. Six feet, whoops.”

The excitement about the photographs, the palpable thrill that pulses through these letters as they fashion a long-distance friendship, the enthusiastic immersion in kitchen lore and technique, the energy of the women’s effort at transatlantic translation of local customs—all speak of an art of conjuring that is cheering to discover in these letters, despite that fact that such resourcefulness moves further out of our twenty-first-century reach with every attention-atrophying wonder of our tap-activated, clickable world.