Territory That I Know

The making of poetry, paintings, and Umwelt.

I received an email from my friend, the painter Ellen Wiener, in which

she mused upon the global reach of her grown children’s curiosity

compared to the more focused and, as she acknowledges, Eurocentric

purview of her own. “We are sliding,” she wrote, “and in most ways

rightly so, into a much more global awareness. My children want to visit

Mexico City, Japan, India . . . and my inspiring explorations are

apparently in some London of 1785.” With the kind of sympathetic magic

that has graced our correspondence for more than a quarter-century, her

message arrived as I was spending a concentrated block of time each

morning in something like the same historical neighborhood as she,

albeit a dozen years later and some 130 miles to the west. If she has

been figuratively cultivating botany at Kew and admiring the

recognitions constellated at the museum of Sir John Soane*, transforming

both into gem-like images that float in time and space with elemental

grace and uncanny gravity, I have been wandering the Quantock Hills with

two youthful poets and assorted companions in the pages of Adam

Nicolson’s The Making of Poetry: Coleridge, the Wordsworths and Their Year of Marvels.

The

year of Nicolson’s title, which straddles 1797 and 1798, saw, in the

author’s estimation, a transformation in the human imagination. The

vehicle for this revolution was a small volume entitled Lyrical Ballads, in

which the otherworldly (“The Rime of Ancient Mariner”) and the

conversational (“The Nightingale”) flowed from Coleridge’s quill and

Wordsworth brought his lofty brow to bear on humble characters and

naturalistic scenes, translating them into vernacular verse that gave

English literature a new vocabulary and syntax of seeing. “These

months,” writes Nicolson of the period his narrative ambles through with

knowing appreciation of its natural setting and creative climate,

are when Coleridge started to develop his theory of imaginative education, of a mind shaped by the image-filled worlds into which a child can disappear; and Wordsworth began to discover the opposite, of childhood as the realm not of creative freedom but of unadulterated experience, of moments and spots of time that burned themselves into a child’s being, so that memory became the sculptor of the person.

I

can’t easily dismiss the book’s claims for the poet’s reach, for it’s

those two orders of apprehension that, on reflection, have shaped my own

perception, if not understanding, of presence in the world, although I

never recognized it so clearly until Nicolson provided the lens to see

it. That the lens is that of poetry, and 200-year-old poetry at that,

only augments the worrisome sense of anachronism that has had me

wondering what exactly is the point of immersing myself, via Nicolson’s

literary labor, in the notebooks and discarded drafts of Coleridge and

Wordsworth as, day by day, in whatever direction one happens to look,

the country seems determined to go to hell in a handbasket. Not for

nothing did I copy out Ada Calhoun’s description, in her recent memoir, Also a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me, of

her exasperation as she listened to some of the decades-old interviews

her father had conducted with Frank O’Hara’s self-absorbed New York art

world contemporaries: “Why was I still listening to these people talk? I

needed to focus attention on the present, where my father might be

dying.” My father might be dying, too—is certainly dying,

sooner rather than later, but nonetheless resort to the Quantocks has

consoled me as I struggle with the paradoxical enervations, both patient

and urgent, of his care, ignoring the anarchies loosed on larger lives

as I tend one small, dear one.

“To them I may have owed another gift,” writes Wordsworth in the last poem in Lyrical Ballads,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened:—that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

If

I’m honest, the consolation I take from literary endeavors in the

present fraught moment is just a happy byproduct of what I’d be doing

anyway, because savoring the sentences of other writers, or turning my

own around, are what my mind and heart have become habituated to in the

course of nearly seven decades. Having learned to do both to at least a

private level of satisfaction, they form, after all this time, the

landscape I inhabit.

The epigraph to The Making of Poetry is a quotation from a radio interview with Seamus Heaney:

The making of verses, the making of works, occurs in the edges of your life, of your time, in your late nights or early mornings . . . And my words, the words for me, seem to have more nervous energy when they are touching territory that I know, that I live with . . .

All

our thought and feeling, whatever the venue we use to capture it, is

more vivid when it touches territory we know; most of us, in the age of

uprooted, portable relations in which we are both blessed and cursed to

abide, do not inherit that territory but have to construct it. As those

constructions age and weather, or are overtaken by the flotsam and

jetsam of the rising newsfeed tide, they seem less resilient, more

defensive, less ingenious and spontaneous than they once did. I feel

more and more provincial every day: what once seemed an admirably and

oddly eclectic set of interests—right now circling around the paintings

of Joan Mitchell, the letters of Sylvia Townsend Warner, the films of

Agnès Varda, obscure corners of the string quartet repertoire—seems

increasingly parochial, as if I’m the parson of some rural church

tending gravestones whose inscriptions grow fainter with each passing

week.

Ellen

and I are roughly the same age, so I suspect some of the vocational

fixity she ponders in herself as she admires her children’s wanderlust

is the result of the natural seasoning of impulse. But she is on the

track of something more profound: the way the traditions on which our

skills—more tellingly, our intuitions—have been nourished can begin to

feel antique; not just venerable, but brittle. With comic ruefulness,

she tells me how unused digital drawing instruments—gifts from her

son—scold her from a nearby shelf as she goes about her habitual

business: “I sharpen cylinders of graphite. Guilty.”

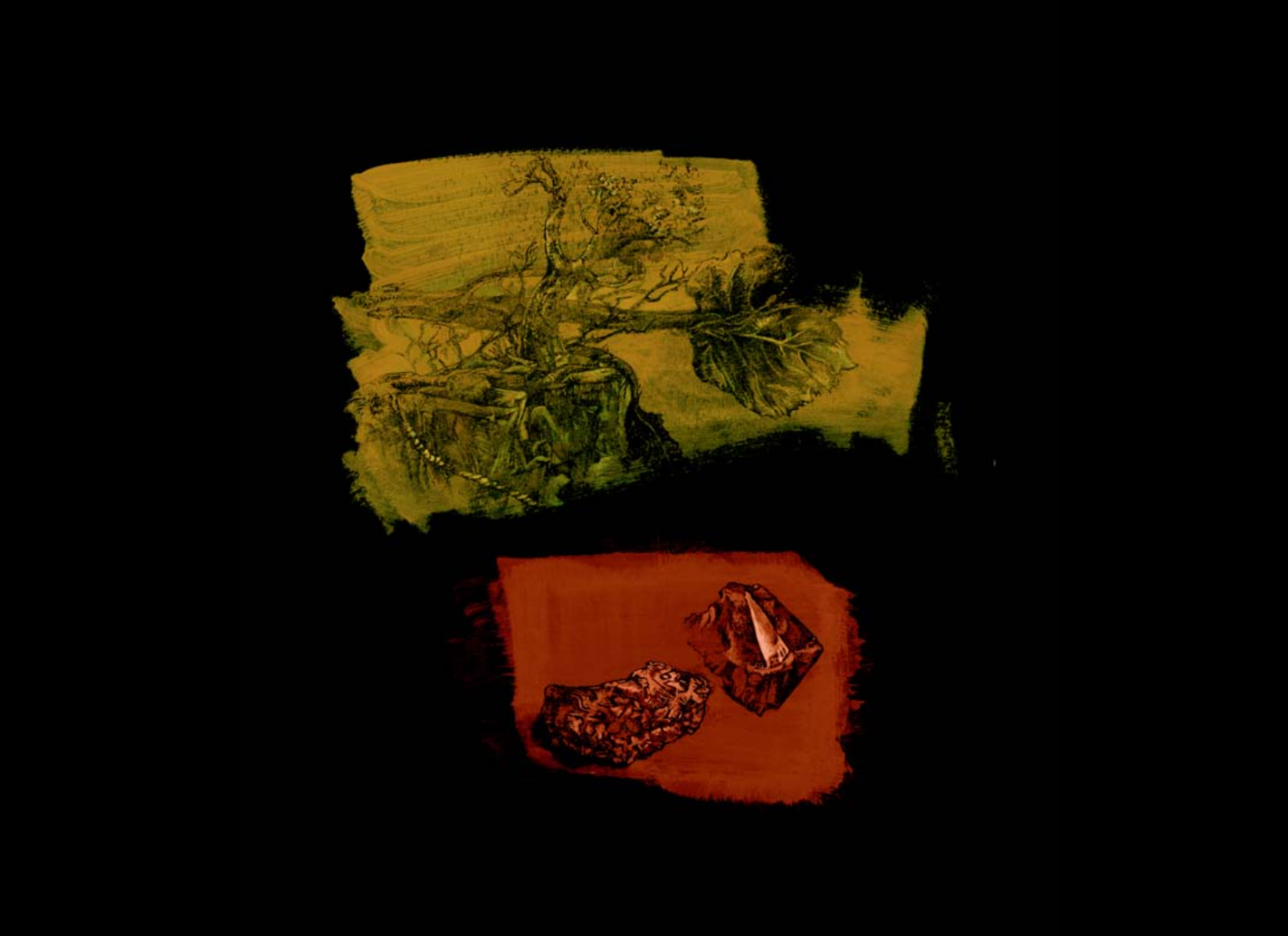

What she does with those cylinders of graphite, on the other hand, is filled with the innocence of inspiration, tempered by the long sentences the work itself hands down with its own inescapable judgement. First is the drawing, she tells me when I ask about how Leaf & Underlain, spied on Instagram (@ellenwienerart), is made:

Detailed pencil studies of rocks, plants and landscapes—as in

These are then transferred lithographically by hand or on the etching press (surely you don’t want the chemistry?) onto a colored ground and painted. Then scanned, resized, recolored & tweaked in photo shop. Then printed using Epson 900 inkjet. Then hand colored again with gouache, colored pencil, pastel and oil. All on paper.

Leaf & Underlain is one of a group of works Ellen calls “Bigeminals” (you can see them all at her website), because

it embeds the word GEM but also because there is a break, a stutter between the images—as each pair needs a heartbeat of blank before the looker can begin linking the fragments. Each “duet” can be seen as the landscape and what essential ingredients & elements lie underneath.

Floating

on their black ground, the Bigeminals strike me as minerals mined out

of thin air. They have the heft of rock and the ethereal beauty of

jewels you can see into, light leading you through long vistas of

formation with its frolicsome poise, time unleashing all its tenses in

the same moment of looking. They’re like specimens from the field

sketchbooks of Gabriel García Márquez, if he had only been a fossil

hunter (which, come to think of it, he was).

“I

guess what I’m trying to illustrate are miniature myths,” Ellen

explains to me, “. . . the mood is poignant though—as in looking at

souvenirs.” In this context, the word souvenir unfolds in time, unwinding its history from its current meaning of “memento” through its French forebear in the verb se souvenir—to keep the trace of someone, something in memory—and back to the Latin subvenire:

to come to help, come to mind. The nervous energy of which Seamus

Heaney speaks, that animates words into poetry, is found along the roots

of that etymology, in the coming to mind that comes before souvenirs

become commodities, when they move like creatures through the

imagination. There is a cryptography to consciousness: a thought

Coleridge, if not Wordsworth, would have loved to ponder.

I

discovered a word recently and, with the serendipity fresh knowledge

invites, now seem to be stumbling upon it everywhere. It was coined by

the zoologist Jakob von Uexkűll, who, in the years between the two world

wars of the twentieth century, “transformed the study of animal

consciousness,” as David Trotter recently wrote in the London Review of Books (in

a piece, believe it or not, on Sylvia Townsend Warner), “by

demonstrating that all organisms experience life in terms of a

species-specific, subjective, spatio-temporal frame of reference

uniquely adapted to the environments they inhabit. He called this frame

of reference an Umwelt, or immediately surrounding ‘world’.”

It’s no different for human beings, as far as I can see: our Umwelt is

the territory we know. There we wander, sometimes without leaving home,

among all the souvenirs that we’ve assembled, or are assembling us:

Ellen sharpening graphite cylinders while I deploy semicolons not so far

away, on the other side of Long Island Sound.

❖

*Note on Sir John Soane: At 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, facing the largest square in the city, an elegant small house conceals behind a modest façade the most remarkable and personal museum in London, perhaps in all the world. Its creator had an extraordinary career: beginning as a bricklayer’s boy, John Soane (1753-1837) became an eminent architect whose innovative elaborations of Greek and Roman motifs produced such influential buildings as the Bank of England and the Dulwich College Picture Gallery. Bequeathed to the nation by its owner upon his death, Sir John Soane’s Museum is crammed with sculptures, paintings, and curiosities that occupy every available inch of wall and floor space. The Picture Room, for instance, a chamber of modest dimensions, is designed with such ingenuity that it contains more than 100 works—including compositions by Canaletto, Piranesi, Hogarth, and Turner—arranged on walls that are hinged screens, each opening out to reveal new layers of paintings and drawings behind. All in all, the museum is a wonder-cabinet bursting with astonishing contents and cultural resonances, including more than 7,000 books, a seemingly endless supply of artifacts and antiquities, and such singular items as the sarcophagus of the Egyptian pharaoh Seti I.