RIP Pete Hamill

Remembering a writer, reader, and friend.

In 2007, some time after the end of A Common Reader, my friend Steve Riggio, then CEO of Barnes & Noble, asked me to start a book review on the company’s website. He gave me the best brief an editor ever had: “Make a site that you and I would go to to find something interesting.” And so a new round of deadlines, daily at first, came into play with the Barnes & Noble Review, although there was less pressure for me to write than to assign and edit reviews. Matching writers to books was one of the pleasures of the job, especially when we were able to lure a celebrated author with a well-chosen assignment. That’s how I met Pete Hamill.

Knowing Steve knew Pete, I’d asked for an introduction, and followed up Steve’s email putting the two of us in touch with this one of my own. It’s dated February 11, 2009.

Dear Pete Hamill,

I asked Steve to introduce us because I was several pages into the galley of Colm Tóibín’s forthcoming novel, Brooklyn, when I posed the question I’ve been asking since Steve gave me the chance to develop the B&N Review: “Who would I like to read writing about this book?” Your name came immediately to my mind. The book is set in Brooklyn and Ireland in the 1950s, and seems an interesting departure from Tóibín’s last novel on the life of Henry James, The Master. So if there is any possibility you’d consider reviewing it for us, I’d be thrilled.

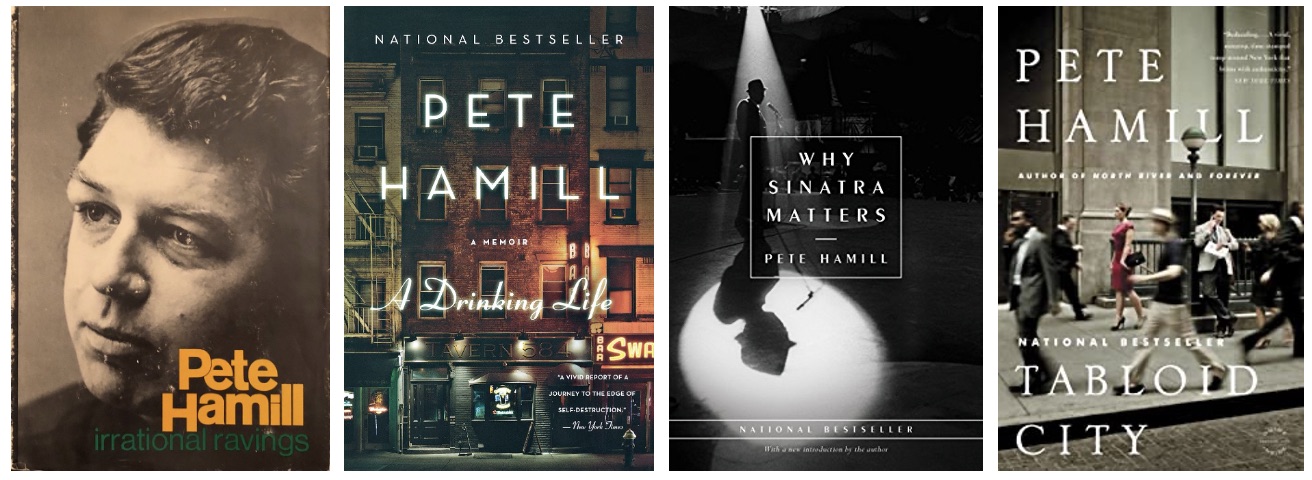

And since I have the opportunity, I’d like to take advantage of it to tell you how much your work has meant to me over the years. Across the room on a shelf I can see a copy of the hardcover of Irrational Ravings I’ve had for nearly four decades (jesus!) now, since I first was on the lookout for writerly models, and next to it the copy of The Gift my mother gave me one Christmas long ago. She chose it because she knew it spoke truly about the perilously indirect conversation between fathers who had graduated from the school of hard knocks and sons who had enrolled themselves, however wishfully, in the school of eloquence. My mother was the reader in the family; I don’t think my father has to this day read a book. He owned a bar for most of my formative years, and your A Drinking Life evoked that world (one I recall with enormous fondness) in a way particularly meaningful to me. There have been a lot of books about drinking, and not drinking, but I’ve never read another so alert to one of the great realities of bars—of American urban life in general, I think. It’s a reality that the drinking often masks and mystifies, but never quite comprehends: the ineluctable, emotionally fraught struggle between the camaraderie and certainties of the neighborhood and the exhilarating, liberating loneliness of a wider world—a bigger fate one can glimpse through reading, but grasp only by leaving. In short, you’ve illuminated the lives of my parents for me better than any other writer I’ve read, and I’ve read a lot. That you’ve therefore had a hand in explaining myself to me goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway, with admiration and thanks.

Hope you don’t mind the fan letter—and if you have any interest in reviewing the Tóibín book, just let me know and we can discuss the details.

Cheers,

Jim Mustich

His reply, which arrived a mere twenty-four hours later, invoked a newspaperman’s sense of time: “Sorry for the delay,” it began. “I’m holed up in Mexico until next Tuesday, Feb 17, writing hard on a new novel.” He went on to thank me for the enthusiast’s part of my query email: “Somehow, we often lose track of our writings, engrossed in the difficulties of the new. Your letter was a reminder that the books remain alive long after they were written, always an uncertain hope.”

He went on to comment upon book reviewing in general with characteristic literary learning and pragmatic wisdom:

Particularly in these hard, shrinking times . . . it would be great to assemble a team of reviewers who don’t think that books are only published to provoke snarky remarks. Or to be subjected to prosecution. It should be possible to be critical and celebratory at the same time. The reviewers I learned from as a writer—VS Pritchett, Edmund Wilson, John Updike, Wilfrid Sheed—managed to do that, even when taking second looks at classics (throw in Italo Calvino here). As fiction writers writing reviews, they were like watchmakers who knew the difficulties of making watches, and would look at the other guy’s watch, and say, you know, if this gear were down here, and that screw up there, the watch would work better. They understood the author’s ambitions and his or her craft, and taught the rest of us about both.

So yes, I’d be delighted to review Colm Tóibín’s novel called Brooklyn. I don’t know the man, and haven’t read all of his work (I do have the Henry James novel on my Must Read shelf, waiting for the moment). It will depend, of course, only upon deadlines, and space.

Deadlines, and space: a good title for a working writer’s memoir.

Over the next couple of years, Hamill and I had a friendly correspondence, always circling around writing and books, but never pinned down to the assignment at hand (after doing Brooklyn, I recall, he wrote a magnificent piece on E. L. Doctorow’s Homer and Langley for us). Three or four times, we met for lunch. On the first occasion, Hamill and I were standing outside Union Square Café, then on 16th Street, waiting for Steve to join us, when Peter Workman, who’d signed me up to write 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die a few years earlier, approached the restaurant. When I introduced Peter as my publisher, Hamill inquired what my book was about, and we outlined the project for him. The next afternoon, I received his own list of twenty “books to read before you die.” Here it is:

- Flann O’Brien: At Swim Two-Birds

- Carlos Fuentes: The Death of Artemio Cruz

- Italo Calvino: Invisible Cities

- James T. Farrell: The Studs Lonigan Trilogy

- Machado de Assis: The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas

- Balzac: Lost Illusions (still the best novel about journalists)

- E. L. Doctorow: Ragtime

- José Camilo Cela: The Hive (La Colmena)

- Ray Bradbury: The Martian Chronicles or The Illustrated Man

- Cesare Pavese: This Business of Living (diaries)

- Stendhal: On Love

- Robert Musil: The Man Without Qualities

- Georges Simenon: The Train or The Premier or The Cat

- Aristotle: Ethics or Poetics

- J. P. Donleavy: The Ginger Man

- Malcolm Lowry: Under the Volcano

- Jack Kerouac: On the Road

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Nausea

- Cyril Connolly (Palinurus): The Unquiet Grave

- André Malraux: The Voices of Silence

The list was as delightful and surprising as the man himself. It arrived without commentary on the individual books, except for Balzac’s Lost Illusions, which Pete annotated as “still the best novel about journalists,” an opinion he reiterated some months later, when he recommended it to my daughter, Emma, who was considering a career in journalism. “Let’s have lunch with Pete and see what advice he has,” I’d suggested to her, and Pete gladly agreed to meet us at Basta Pasta on 17th Street, a mutual favorite, and one that Emma had been frequenting since she was about four.

Read Balzac he said. And Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry to see how to put a story together. “Always work with an editor,” he said in the less literary, more practical part of the conversation, “and don’t write without getting paid.” Be gracious with your time and talent when you find it, he might have added, although he modeled that so well I guess he didn’t need to say it aloud.

The same afternoon, by coincidence, I had to go uptown to interview Gay Talese about a forthcoming book. “Hamill sends his regards,” I was tickled to be able to say as I introduced myself. “I just came from lunch with him.” Talese’s three-piece reserve was breached. He smiled and said, “I went to his high school graduation a few weeks ago.”

He then explained the backstory: two days after Hamill’s 75th birthday, and 59 years after he’d dropped out of Regis High School as a sophomore, the Jesuits who run that prestigious institution gave him an honorary diploma. “The Jesuits,” Hamill said in a New York Times report on the festivities, “believe in taking their time on the big decisions.” (In the long lens of eternity that focuses their everyday opportunism, I suppose the Jesuits can afford to ignore shorter deadlines.)

The night I learned of Pete’s passing, I watched a baseball game on television with my father. Observing the surreal pandemic panorama of the thousands of empty stadium seats encircling the ball field, I imagined an unwritten Hamill column about a game unfolding before missing fans, evoking the loss of shared experience that impoverishes our discourse and imperils our civic as well as public health. Like his friend and sometime subject, Frank Sinatra, Hamill had a gift for concentrating expressiveness, for wringing from the several minutes of attention a column might demand what Sinatra could mine from the three or four minutes of a song: emotions that reached beyond the boundaries of the form that carried them, emotions the audience had neither the time nor talent to articulate for themselves, and that experience seldom has the concentration to deliver without the effort of some mediating art. Eloquence can do some things that life itself cannot.

The next day, looking through my correspondence with Pete, I came up an email I had sent him in praise of his review of Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend, by James S. Hirsch, which ran in the New York Times Book Review on February 25, 2010. Here’s the closing paragraph of that piece:

The young should know that there was once a time when Willie Mays lived among the people who came to the ballpark. That on Harlem summer days he would join the kids playing stickball on St. Nicholas Place in Sugar Hill and hold a broom-handle bat in his large hands, wait for the pink rubber spaldeen to be pitched, and routinely hit it four sewers. The book explains what that sentence means. Above all, the story of Willie Mays reminds us of a time when the only performance-enhancing drug was joy.

Once again, to borrow an apt metaphor from James Parker, this gymnast of deadline prose sticks the landing. May he rest in that poise, and in peace.