On William Saroyan

The writer who made me want to write.

Upstairs in my parents’ house, in a room off what was, in our teenaged years, my sister’s bedroom, are the remains of the library I assembled through my first twenty-odd years. The rows of spines on the two walls covered with shelves are riddled with gaps, representing in absentia books and authors that traveled with me as I established my own households across the subsequent decades. I stood in the room last night, reviewing my early readerly enthusiasms and the flotsam and jetsam of seas of assigned reading. There were many mass-market paperbacks, among them John Barth’s Giles Goat Boy, Stanley Elkin’s Boswell, and Ishmael Reed’s The Free-Lance Pallbearers; several volumes by Jimmy Breslin and other more literary, less incisive journalists; a row of John McPhee’s modestly virtuosic forays into the New Jersey Pine Barrens, the cultivation of oranges, the building of bark canoes, and other assorted natural phenomena and human arts; a hardcover copy of Kenneth Koch’s Wishes, Lies, and Dreams: Teaching Children to Write Poetry, which I’d always treasured, perhaps because I was its diligent student. In what seemed a separate chapel, there was an altar to the memory of the Beats, with Kerouac devoutly represented by an extensive array of candles, but Ginsberg and Corso and lesser lights still faintly flickering nearby.

Older volumes—the letters of Henry Adams, dutiful secondhand assemblages of Dostoevsky, Henry James, Conrad (including The Rescue: it’s been there for five decades now, still, alas, unread), curiosities of Melville’s career overshadowed by the whale—added flavor to the stock. My mother and I spent many wonderful afternoons back then frequenting library book sales, and no remotely intriguing volume eluded my grasp; consequently, the collection I surveyed resembled an old stamp album, each book an emblem of a voyage envisioned, many of which I never took, the whole room exuding the air of a old volume of brittle-edged, yellowing pages.

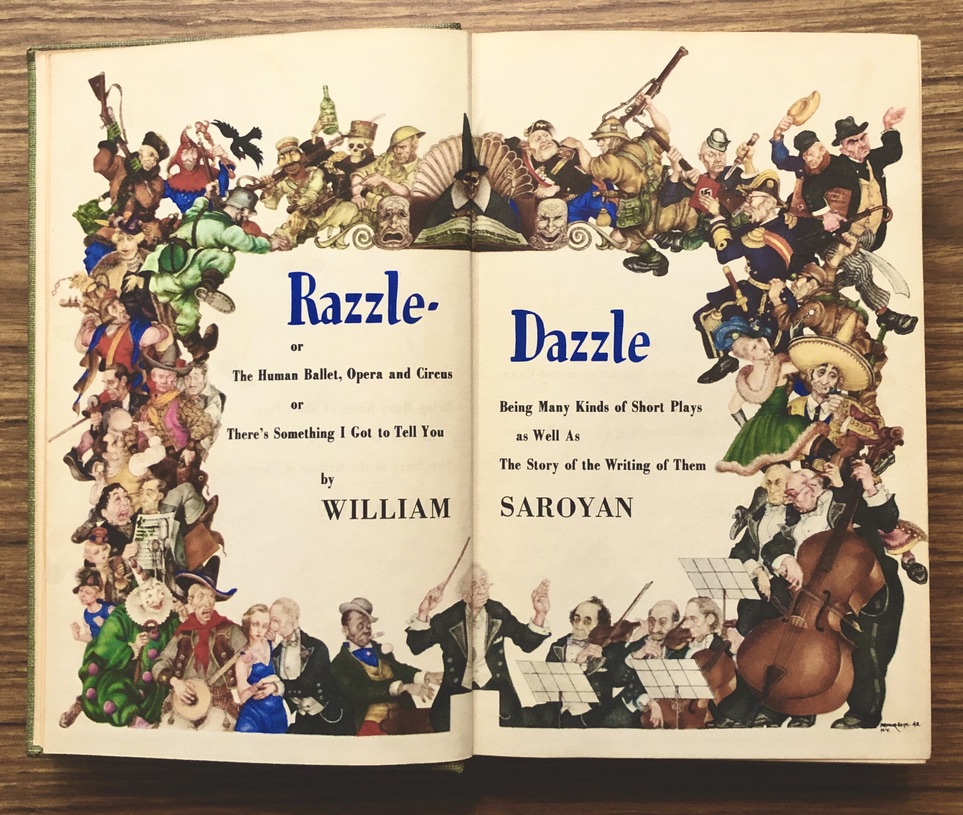

The section of shelf I lingered over longest contained about two dozen books by William Saroyan, the American author of Armenian descent—a pedigree he referenced regularly in his work, and which provided a good deal of the material for his stories and reminiscences, especially in the early years of his career—whose heyday ran from the mid-1930s to the early 1940s, a period in which he was astonishingly prolific, publishing volume upon volume of stories, plays, and novels. His most famous works—the Pulitzer Prize-winning play, The Time of Your Life (with characteristically endearing and perverse bravado, Saroyan refused the award), the autobiographical story collection My Name Is Aram, and the novel The Human Comedy, the latter two, with their seemingly effortless evocation of the fledgling emotions of children, works perfectly pitched for young readers—date from this decade of prodigious (albeit sometimes uneven) inspiration, which found him for a short time mentioned in the same breath as Hemingway and Steinbeck. But several other titles from this period were also at hand as I went through my collection one by one: The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze (1934), which brought his first fame; Inhale and Exhale (1936); Three Times Three (1936); Little Children (1937); The Trouble With Tigers (1938); Love Here Is My Hat (1938); My Heart’s in the Highlands (1939); Peace, It’s Wonderful (1939); Razzle-Dazzle (1942).

His meteoric rise began with The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze, a story collection which opens with a tale called “Seventy Thousand Assyrians.” Actually, it’s more a narrative than a tale, recounting the author’s observation of national mood and human nature as he goes to a haircutting school in San Francisco for a bargain haircut. I don’t think it was the first prose of Saroyan’s I read—I’d place a big bet I began with the autobiographical stories of childhood gathered in My Name is Aram, or his novel of growing up in California during World War II, The Human Comedy—but I got to it pretty soon, and the insouciant swagger of its first paragraph captures the quality that made me eager to read all of his work I could:

I hadn’t had a haircut in forty days and forty nights, and I was beginning to look like several violinists out of work. You know the look: genius gone to pot, and ready to join the Communist Party. We barbarians from Asia Minor are hairy people: when we need a haircut, we need a haircut. It was so bad, I had outgrown my only hat. (I am writing a serious story, perhaps one of the most serious I shall ever write. That is why I am being flippant. Readers of Sherwood Anderson will begin to understand what I am saying after a while; they will know that my laughter is rather sad.) I was a young man in need of a haircut, so I went down to Third Street (San Francisco), to the Barber College, for a fifteen-cent haircut.

“Seventy Thousand Assyrians” is about a writer at work—about being a writer in the world, engaged in a process of translating people and pleasures and passions, small events and big ideas, into prose for the sheer exuberance of expression.

I want you to know that I am deeply interested in what people remember. A young writer goes out to places and talks to people. He tries to find out what they remember. I am not using great material for a short story. Nothing is going to happen in this work. I am not fabricating a fancy plot. I am not creating memorable characters. I am not using a slick style of writing. I am not building up a fine atmosphere. I have no desire to sell this story or any story to The Saturday Evening Post or to Cosmopolitan or to Harper’s. I am not trying to compete with the great writers of short stories, men like Sinclair Lewis and Joseph Hergesheimer and Zane Grey, men who really know how to write, how to make up stories that will sell.

By making so much of his writing about its own performance, by animating it with the brio and intoxication that fuels the imagination, by not looking back to second guess himself but rushing headlong into the next story or drama, Saroyan filled my adolescent soul with a sense of possible vocation that has haunted me ever since.

I am out here in the far West, in San Francisco, in a small room on Carl Street, writing a letter to common people, telling them in simple language things they already know. I am merely making a record, so if I wander around a little, it is because I am in no hurry and because I do not know the rules.

The urgency of utterance, the liberty of creativity, made Saroyan’s early work crackle like fireworks; sometimes it was breathtaking, sometimes just a fizzling without definition, but it was always colorful, and it made the promise of a writing life seem like a dream one could make come true. There have been periods across the years when I was close enough to realizing it—with a small pile of pages as evidence—that I am glad I chased it, however intermittently.

As for Saroyan himself, after his initial explosion across the literary and theatrical sky he more or less faded away as a force to be reckoned with, although his ability to charm readers was never entirely lost. The best books of his later years—Letters from 74 rue Taitbout (1969); Days of Life and Death and Escape to the Moon (1973); Obituaries (1979)—are memoirs about the process of memory, and delightfully desultory. They were on that shelf in my parents’ house, too, until I took them home with me today. His familiar voice on the page, recollecting, with diffidence, happy accidents and squandered chances, putting together sentences to shape his presence in the past and his passing interest in the present, helps me remember myself as I found it in the pages of his early writing, when he wrote like a boy waving at the world in confident expectation of a glad response, until the day—when was it exactly?—it stopped waving back.