Deep Between Covers

Reading Neal Stephenson.

We were away from home for a wedding. With some hours to kill before the convivial festivities began, I found a bookstore in which to spend some quality time with myself, browsing. I thought I’d pick up a slim volume—poetry, perhaps—for intermittent reading through the next few days without adding much heft to the luggage.

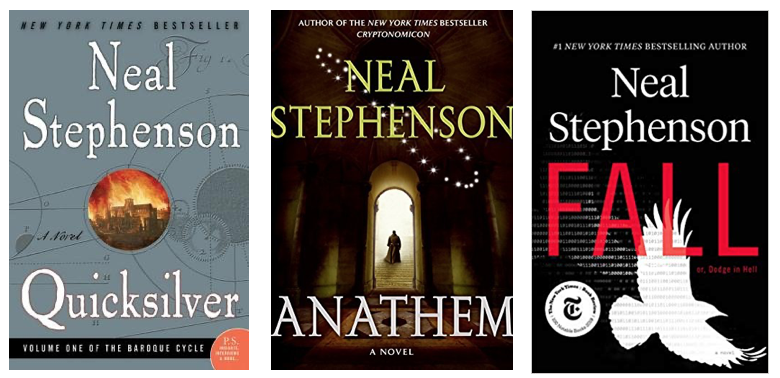

What I walked out with instead was Neal Stephenson’s latest bulky opus, Fall, or Dodge in Hell, billed by its publisher as “Paradise Lost by way of Philip K. Dick.” Standing in the store, I’d read the first few pages, and was—as usual with Stephenson—lured into a current of story, eager to be carried forward.

Back at the hotel, I read the first sixty-odd pages, wading into a narrative river fed by the technological, scientific, historical, conceptual, and imaginative tributaries that Stephenson’s mind travels; sometimes the flow carries the reader straight out to sea for a transporting voyage and sometimes it diffuses itself into a fecund, mysterious estuary it’s hard for either writer or reader to get out of, and which has its own rewards: There’s lots to occupy one’s attention in that delta.

In 2008, I spent most of the summer neck-deep in Stephenson’s work. I’d been led to it courtesy of a collaborator whose taste I respected enormously. At the time, we were editing an online book review, and I was interviewing authors as time and opportunity allowed. When my colleague noted Stephenson had a new novel coming out that autumn, he suggested I try to schedule an interview for the week of publication, thereby committing myself to diving into a body of work he’d been recommending all along.

As I would soon find out, the forthcoming novel, Anathem, running to more than 900 pages, demanded quite a commitment all by itself, especially for a reader not especially familiar with the landscape, or perhaps better, atmosphere of contemporary speculative fiction. Set on a planet called Arbre, Anathem is narrated by Erasmus, a young man who has lived much of his life as a member of an ancient (as in 3,400 years old) monastic community comprised not of religious believers but of philosophers and mathematicians.

Inventing a political and intellectual history, as well as an ingenious vocabulary, for his imagined world, Stephenson composed a work of large speculative dimensions, animated with both ideas and adventure. As the plot unfolds, Erasmus and his confreres are called out of their cloister and into the service of the unlearned, fearsome, technology-infested “Saecular” world to help defend Arbre from the threat posed by the mysterious forces of an alien power.

Once I’d acclimatized myself to its rarefied air (the orientation took me about 100 pages; “That’s a remarkably universal remark,” Stephenson told me when we spoke that September, “almost everyone says, ‘The first hundred pages were heavy sledding, and then it started happening for me’”), I found the world of Anathem so absorbing I tore through the book, and then plunged into more of Stephenson’s fiction: Snow Crash, Cryptonomicon, and the Baroque Cycle, which comprises three volumes: Quicksilver, The Confusion, and The System of the World, two of which I completed over the summer. I even read a short nonfiction book called In the Beginning … Was the Command Line.

By the time the hour of the interview rolled around, a week after Anathem’s publication in early September, I was able to tell the author as we sat down for a chat that I had never read a word of his until a few months ago, but had traversed well over 4,000 pages of it since then, with delight and intellectual profit in equal measure. Completing The System of the World post interview brought my 2008 Neal Stephenson page total closer to 6,000. I hadn’t had so much fun reading in years.

So I fell into Fall with a sense of familiarity, caught up by Stephenson’s ingenious manner and the baroque abundance of his narrative artifice, its inventive assimilation and repurposing of ideas from several realms of thought. Of course, I want to know what happens next as I turn the pages, but the plot is not as rich a reward for the time I’m applying as the ambience. Deep in the folds of one of his books, I struck by a simple thought: “I like being here.”

All of which brings me to Henry James. In a subsequent post, I’ll try to explain why.