Homebound

Late at night with my mother’s favorite books.

I sit in my parents’ living room in the wee small hours of the morning. It’s dark except for the illumination provided by the large television that is my father’s constant companion as he dozes and wakes in his reclining lift chair, ruminating, I can only suppose, on his 91 years as pain and discomfort circulate through his increasingly frail mortal coil. He is keeping vigil for my mother, his wife of nearly 70 years, as he waits and hopes for her to come home from rehab, where she is recovering, first falteringly and now with some hopeful momentum, from a fractured hip.

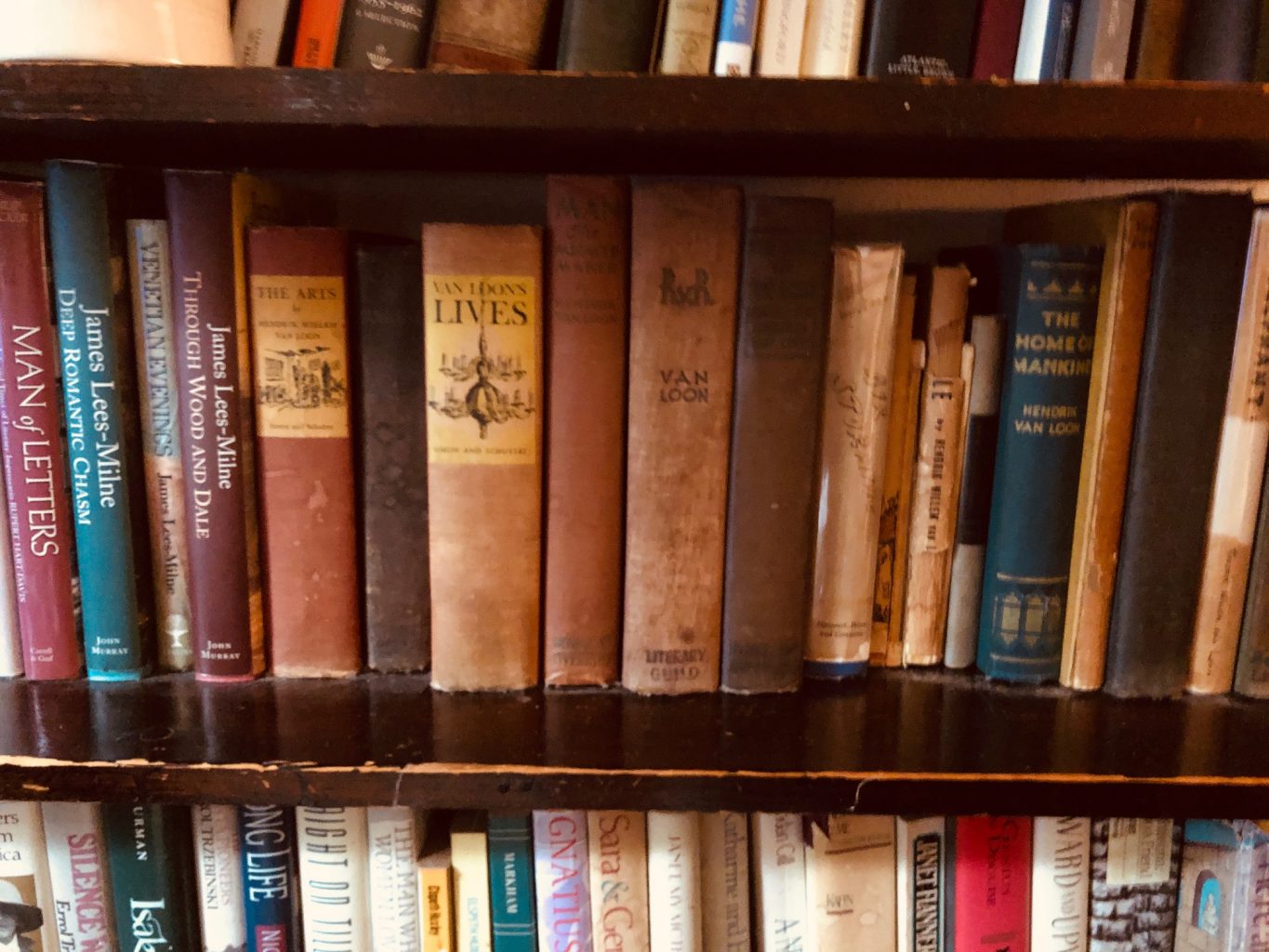

To my right, and behind me, are bookshelves built, before I was born, by my mother’s father. My dad not being a reader, the books that fill them are entirely hers, and as I sit in quiet companionship with him, I trace along the spines a map of her interests and attentions, interests and attentions foreign to the world of her Italian immigrant father whose carpentry still holds them. I remember him as a silent presence handing me scraps of wood to nail together intently as he toiled more productively in his workshop. He spoke very little in Italian and less in English, smoked Parliament cigarettes, never tired of lamb chops, watched the Huntley-Brinkley Report each evening on NBC, and wanted his death notice to appear in The New York Times. While his wife, my grandmother, took secret delight in reading celebrity biographies (as I learned once I entered the bookselling business and could supply her with same at a steady clip), neither of my mom’s parents would have cherished the books I look at now: a shelf of volumes by Dutch-American historian Hendrik Willem van Loon—most notably the ambitiously subtitled Van Loon’s Lives: Being a true and faithful account of a number of highly interesting meetings with certain historical personages, from Confucius and Plato to Voltaire and Thomas Jefferson, about whom we had always felt a great deal of curiosity and who came to us as dinner guests in a bygone year—beautifully produced and illustrated, the kind of volumes a reader can fall into; a complete set of the diaries of Frances Partridge, the last survivor of the legendary Bloomsbury Group, who began to publish them—in which her elegantly composed accounts of her current days are colored with reminiscences culled from her long life in the company of authors, artists, and other fascinating figures—when she entered her seventies; Ann Cornelisen’s Torregreca and Women of the Shadows, about life, death, and miracles in a southern Italian village; the indelible if arguably accurate autobiographical narratives of Lillian Hellman; memoirs, diaries, and letters of Christopher Isherwood and May Sarton; books by and about Dorothy Day, the American political activist, pacifist, and co-founder of The Catholic Worker newspaper and movement, who has lately been put forth for canonization by the church, although she herself would bridle at that idea: “Don’t call me a saint,” Day once wrote, “I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” At the end of one shelf, dilapidated by my mother’s six readings of it, is Robert A. Caro’s massive The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York in its original hardcover edition, which, many years after its release, I got the author to sign for her when I interviewed him (he was thrilled that the book was so palpably well-read).

But the book I take up to peruse tonight in the television’s glow is the one I know to be her favorite, A Mass for the Dead by William Gibson—not the visionary science fiction novelist of the same name, famous for Neuromancer and Pattern Recognition among other works, but the American playwright most celebrated for his play about Helen Keller, The Miracle Worker. Through my mother’s advocacy, A Mass for the Dead became my favorite, too, so much so that, back in the days of A Common Reader, I rescued it from out-of-printness (to which fate, alas, it has been confined once more). In fact, my desire to make it available again was a primary impetus in the decision to launch our own publishing program in 1996, and I was pleased beyond measure when Gibson’s family chronicle, originally published in 1968, became our first Common Reader Edition.

In this eloquent volume, Gibson relates, with affection, anguish, wonder, and extraordinary sympathy, the story of his father and mother: their families and their courtship, their determined yet unspectacular search for economic security and domestic comfort in and around New York City in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, their dedicated parenthood. It is the story as well of the author’s growth from boy to man, from happy child to disaffected youth to father and—as his parents reached the end of their lives—once again blessed and blessing son.

Beginning with a meditation on a missal he finds among his late mother’s effects, Gibson shapes his chronicle to the image of a requiem mass, interspersing his continuous narrative with passages of evocative, powerful, prayerful contemplation as well as bursts of knotty poetry. In doing so, he fashions a language lofty enough to honor the generosity of life’s generations, yet supple enough to capture all the commonplaces—of parents and children, affection and argument, birth and death—that those generations inhabit. The fruit of his effort is a book that has haunted my imagination with the force of life itself in the four decades since I first read it, a book whose rendering of experience so gracefully shaped what I knew, or intuited, about existence that my sense of self, family, and world would be unrecognizable to me— and no doubt impoverished—without it.

My mother, I know, feels as strongly about the book; she badgered me to read it for years before I—being young and lost in those nether reaches of poetic ambition which keep one at a distance from family, a distance which Gibson so tellingly describes—finally deigned to do so. I’ve returned to his pages many times since that first reading, most tellingly in the new light cast by the two girls who ushered me into fatherhood, and each reading has made me appreciate all the more profoundly my mother’s love for this work, leaving me astonished anew at how extraordinary, how genuine and true, are its sentiments.

Tonight’s no different: flipping through the pages of A Mass for the Dead,I am brought up short by shocks of recognition as Gibson portrays his family’s passage through the weatherings of time. Brooding on my father’s fitful form, praying for my mother’s recovery in a lonely room fifteen miles away, I am brought near tears by passages like this:

Of that tissue I was born, saw what I saw, the betrayals and the gifts, take nothing on hearsay, and know the lives of my father and my mother, laboring to survive in self-respect; all that I see is true, and insufficient. History is another book, and its last page may be ashes. Yet the first page I read was the avowal of growth in eyes which, over me and my sister in cribs, made our survival their credo until from beyond the grave my mother said, “I loved you both dearly.” Of that tissue, predicting murder or mercy, life or extinction, and allowed one belief, half tonguetied, what dare I say?

I believe in my parents. I believe in my parents, therefore, in myself, therefore, in my children. I believe in my parents, and in life everlasting.