Face to Face with John Singer Sargent

An intimate viewing at the Morgan Library.

I was in the Cleveland airport a couple of months ago when I got a call from one of my oldest friends. Being old enough now that most of my old friends are in fact old, picking up an unexpected call is always shadowed with a little trepidation, so I was relieved, and happily surprised, to hear that he was calling from the Morgan Library in Manhattan to encourage me to see the exhibition of charcoal portraits by John Singer Sargent that had just delighted him. His recommendation came with a specific instruction: look at the drawings from twelve inches away.

In the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day I finally got to the Morgan. The show, as promised, was revelatory. The gallery that held it gathered maybe three score of the likenesses of friends, social celebrities, and artistic luminaries that the artist, having wearied of his phenomenally successful career as a portraitist in oils, had taken to drawing in single sittings lasting three hours or so. Even at a glance, Sargent’s preternatural skill was apparent, bestowing upon each figure a reserve of personality almost as striking as the draughtsman’s facility. The human nature on display was stunning in its variety and exactitude.

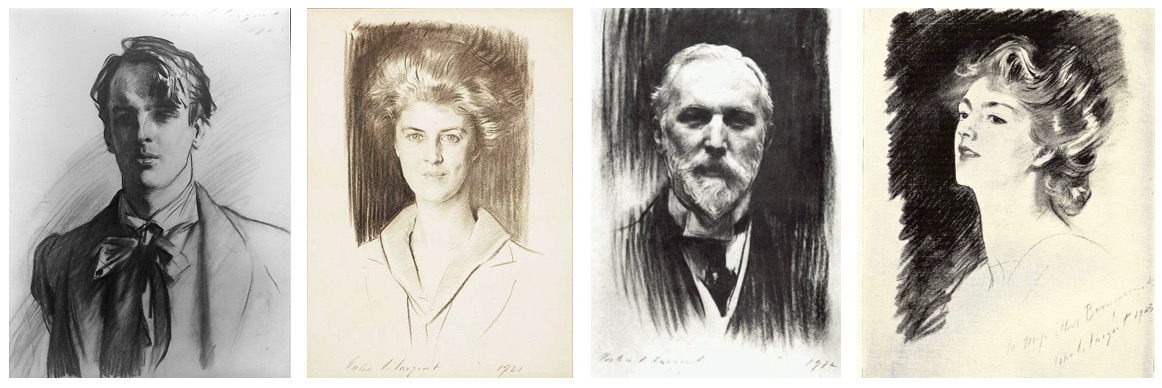

I took a quick tour around the exhibition before following my friend’s advice, admiring from a few feet away the portraits’ beauty and declarative eloquence. The young William Butler Yeats, for example (at left in the row of images at the top of this post), seemed to emanate from the shadows of poetry itself, finding his vocation within the frame. Further along the same wall, the socialite athlete Eleonora Randolph Sears (next to Yeats) locked the viewer’s attention with a magnetism strong, alluring, confident. Around a partition, tucked in a corner, Robert Henry Benson (second from right above), banker, Trustee of the National Gallery, and patron of the artist, exuded an alertness that suggested he’d be a fit protagonist for a dramatic as well as a commercial enterprise; I had a suspicion that, from across the room, another Sargent subject, Henry James, had his novelist’s eye on Benson.

Then, my friend’s insight in my ear, I began a more intimate inspection. Generally speaking, pictures can lose definition the closer one gets to them, thereby gaining a different kind of visual interest, one that is enhanced once one steps away again, allowing the imagery or larger architecture of the composition to come into broader focus, sometimes magically. Which is to say that normally we like to step back to get the full scope. Not with these portraits: their imaginative dimensions, their compositional fluency, increased as one approached, so that one witnessed an intensifying not only of focus but also of character, as if who the person was had been conjured by concentration and transmuted into an image both more supple and more permanent than flesh. All portraits are supposed to do something like this, of course; in these by Sargent, from twelve inches away, you could watch it happen: face after face captured by his gaze, fixed in time but just as uncanny in its possession of its subject as the picture of Dorian Gray.

[Note for completists: the fourth image at the top of this post is Sargent’s portrait of the young Ethel Barrymore.]