An Exchange of Gifts

A Classical Education, part five.

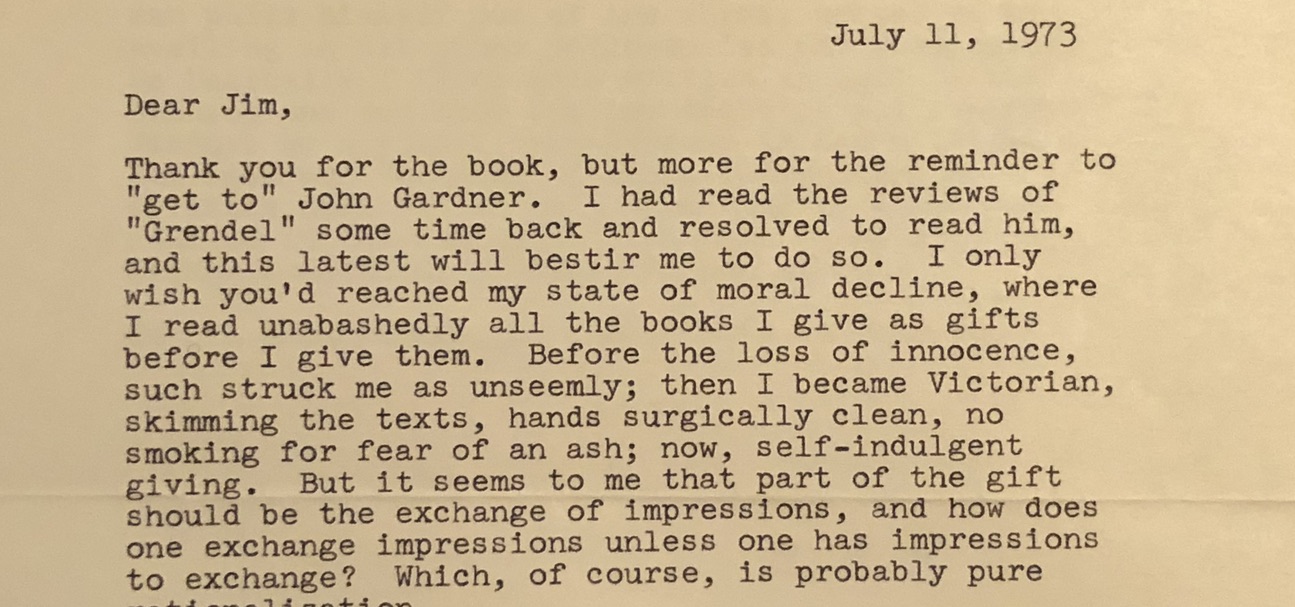

In gratitude for the Harper’s Dictionary and all it represented, and out of a politeness I knew he would appreciate as much as the gift, I sent Mr. DaParma a book: John Gardner’s then recently published epic in verse, Jason and Medeia, a retelling of the classic mythological tale of heroic endeavor, ill-starred passion, and unfortunate children. Some weeks later, I received a letter—it’s dated July 11, 1973—that was not only a thank you but also a capsule review. It started with characteristic wit:

Thank you for the book. . . . I only wish you’d reached my state of moral decline, where I read unabashedly all the books I give as gifts before I give them. Before the loss of innocence, such struck me as unseemly; then I became Victorian, skimming the texts, hands surgically clean, no smoking for fear of an ash; now, self-indulgent giving. But it seems to me that part of the gift should be the exchange of impressions, and how does one exchange impressions unless one has impressions to exchange?

Later in the same letter, having described a dutiful embarkation upon Gardner’s verse voyage, and annotated the description with examples of lines “I kept wincing at,” he wrote:

. . . I smiled along until I realized that the poetry had become consistently good and he seemed to have a good epic-tragedy going, with an existentialist hero headed toward doom. Then, at the climax, the hero is revealed as a fraud, and existentialism, the rope whereby modern man pulls himself out of the abyss, proves as unavailing as all of the philosophies and theologies.

What has proved availing, for me at least, is the learning that began back in those Latin classes, the slow simmer of study, inspiration, and expression that I have grown fond of epitomizing in the method of the periodic sentence, which—according to William Harmon’s A Handbook to Literature, the reference companion required for my high school English course, still on a shelf in my home library—is used “to arouse interest and curiosity, to hold an idea in suspense before its final revelation.” Like a sentence that’s complex and purposeful, an education unfolds in time, articulating ideas and holding them in relation to one another in a kind of gravity, composing them into emergent patterns until a fresh burst of energy—connection, direction, contradiction—snaps disparate views into a new vista that extends the range of your attention and, with it, the store of meaning available to you. “Truth happens to an idea,” wrote William James; the same can be true of a sentence—and a life, if it learns the resourcefulness to honor its doubts, revise its infelicities of character, accommodate the qualifications of self-regard and the hesitations every emotion puts in its path.

In another letter, after praising a piece I’d published in the school’s literary magazine, Mr. DaParma chides me for its title, meant to evoke Horace’s description, in the Ars Poetica, of how the epic poet situates the reader, from the start, in medias res: in the middle of things. In my sloppiness, I’d named my prose poem, “In Media Res,” thus dispensing with the case agreement between “middle” and “things,” rendering it, as C. W. D., noted with stern kindness, “unintelligible in Latin.”

Some scholar I turned out to be, informed by my learning but all too often confused as to its application. As I suspect many of us are, in the middle of our life sentences, keeping our minds in a state of uniform or increasing tension as we await the dénouement. Most that we hold dear—faith, hope, and love, family, children, and even fortune—must be grasped in medias res, day by day, or their meaning for us finds no intelligible expression at all.

At the end of the note that accompanied his gift of Harper’s Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities, C. W. D. wrote: “We never talked, always fenced, but there was always something ineffable, at least from this side.” From this side, too. If all I could offer at the time was fencing, it was likely because I didn’t know how to manage anything else: How does one exchange impressions unless one has impressions to exchange? That’s the conundrum facing any young person with a ready wit and a feel for words who is a neophyte at making meaning. If I’ve advanced in the school of eloquence in the decades since I took home that ancient dictionary, and can now, as I approach old age, put words around what was ineffable from my side then, it is in no small part due to what I learned—or what I learned how to learn—in the study of Cicero’s carefully composed sentences fifty years ago, and which I’ve taken for granted—and, thanks to the gift of Mr. DaParma, as granted—ever since.

_______

More of A Classical Education: