Alone Together: The Civility of Reading

An address at Transylvania University, 10.18.18

Good afternoon. I’d like to thank President Carey and the university for inviting me to speak to you today as part of the Creative Intelligence program. I appreciate the warm welcome, and I would especially like to thank each of you for coming to listen.

This afternoon I’ll be speaking about who I am, and tell you a bit about the book I’ve written. And then I’ll use aspects of that book’s content and themes to share some thoughts that I hope you’ll find relevant to Transylvania’s campus theme of civility.

I’ve been an avid reader for six decades now, and a bookseller, too, for four of those. My book, 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die, is a testament to those pursuits. In writing it, I wanted to make a record of what I’ve loved as a reader and what I’ve learned as a bookseller. Like all dedicated booksellers, I view the job as something of a vocation, In the words of Roger Mifflin, the bookselling protagonist of Christopher Morley’s Parnassus on Wheels and The Haunted Bookshop, two marvelous novels from the early 20th century that have made their way into my 1,000, dedicated booksellers seek “to spread good books about, to sow them on fertile minds, to propagate understanding and a carefulness of life and beauty.”

“A carefulness of life and beauty” is one way to view civility. But more on that in a moment.

I’ve spent fourteen years writing 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die, and in some of those years I wasn’t entirely convinced I was going to finish it the before the terminal event invoked in its title came to claim me. But here I am, book in hand. And now that I’ve finished it I expect to spend the next fourteen years traveling around to bookstores, libraries, and venues like this hearing from readers like you what I’ve got wrong. I hope we’ll get to some of that at the end of my talk when we open the floor for questions and conversation.

And it’s something I very much welcome, and am quite used to by now. For once people know you’re writing a book called 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die, you can never enjoy a dinner party in quite the way you did before.

No matter how many books you’ve managed to consider, and no matter how many pages you’ve written, every conversation with a fellow reader is almost sure to provide new titles to seek out, or, more worryingly, to expose an egregious omission or a gap in your knowledge—to say nothing of revealing the privileges and prejudices, however unwitting, underlying your points of reference.

While I hope my recommendations are useful to people, and fun for them to explore, I know all readers will use their own agency in alighting upon their next book. In fact, one of the first things you see when you open mine is an epigraph from Virginia Woolf, drawn from her essay, “How Should One Read a Book?”

“The only advice,” Woolf writes, “… that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess.”

I’ll venture to say that “independence” and “agency” also belong to the word cloud that surrounds the idea of civility.

Before I talk more about that, let me give you a brief description of what my book is: 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die is 1000 brief, informative, and—I hope—entertaining essays on 1000 books which range in time from the Epic of Gilgamesh, encoded on tablets in Babylon some 4000 years ago, to Ellen Ullman’s Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology, which was published in 2017.

The books range in provenance from the classical to the commercial, in mood from the wisdom of Plato to the wit of Dorothy Parker, in style from stateliness of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice to the millennial hipness of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. My selections are about 50% fiction and 50% nonfiction, the former encompassing mysteries and entertainments as well as literary fiction, the latter consisting of a broad range of subjects from biography and memoir to travel and food and science, philosophy and religion and poetry. And since my title invokes a lifetime’s reading, there are plenty of books from children and adolescents. In fact, one might follow a reader’s life in my pages from Goodnight, Moon and Where the Wild Things all the way to Simone de Beauvor’s The Coming of Age and Joan Didion memoir of mourning, The Year of Magical Thinking.

The book is not prescriptive, but inviting: I hope readers will open it anywhere and, as the poet and critic Randall Jarrell once exhorted us, “Read at whim! Read at whim!” I like to think of it as a big menu, because I believe readers read the way they eat—hot dogs one day and haute cuisine the next—and I wanted it to speak to every kind of reading appetite.

A thousand books felt for years like far too many to get my head around, but now it seems too few by several multiples. So let me say what already should be obvious: 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die is neither comprehensive nor authoritative, even if a good number of the titles assembled in it would be on most lists of essential reading. It is meant to be an invitation to a conversation—even a merry argument—about the books and authors that are missing as well as the books and authors included, because the question of what to read next is the best prelude to even more important ones, like who to be, and how to live.

And that’s where I think my work begins to intersect with the theme of civility.

For running through the book, like a steady current connecting all the discrete essays, is a lifelong rumination on why we read, and how the traditions, technologies, and culture of the book have enriched our individual and collective lives, especially compared to the world of screens and algorithms in which we are, like it or not, increasingly at home. How does all this—and especially the products of the age of the book, which supply the matter of mine—resonate with the theme of civility?

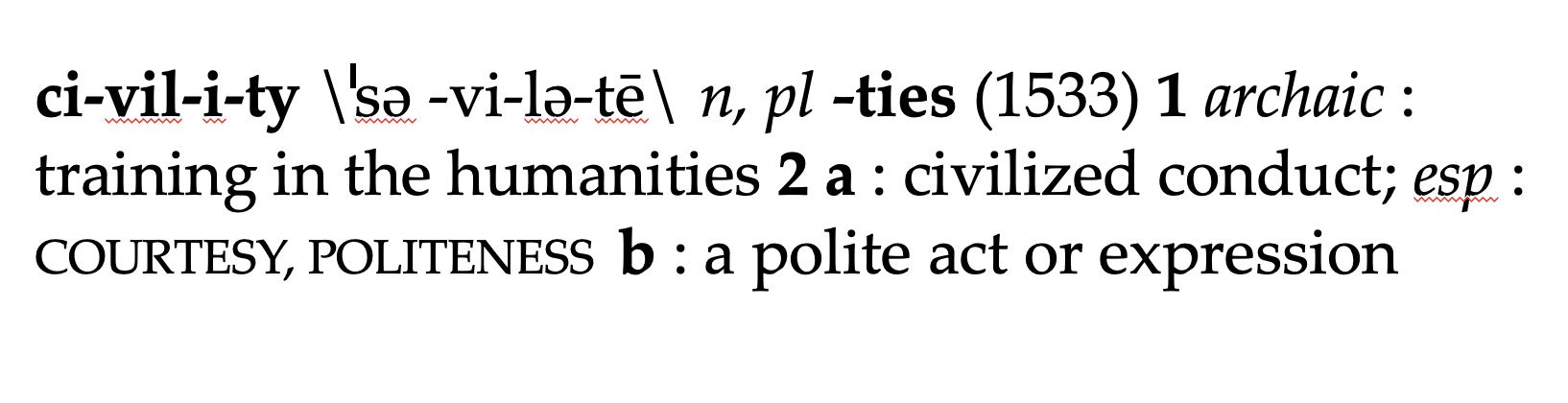

Let’s leave my book and go to the dictionary.

In Merriam Webster, we find 3 meanings for “civility”: the first, labeled “archaic,” is: “training in the humanities.”

The second is “Civilized conduct, especially: courtesy, politeness.”

And the third is “Formal politeness or courtesy in behavior or speech.”

You can trace the same evolution, or devolution, through historical examples in the Oxford English Dictionary, following the meaning of the word as it narrows from education to etiquette; in this it curiously mirrors the degradation in spiritual fitness described in the Tao Te Ching, or Way of Life, composed in China somewhere around the mid third century before the common era. In Witter Bynner’s translation of this influential and resilient work of spiritual guidance, the 38th section, which is actually the first section in the oldest manuscripts, reads:

Losing the way of life, men rely first on their fitness;

Losing fitness, they turn to kindness;

Losing kindness, they turn to justness;

Losing justness, they turn to convention.

In those lines, the Tao presents a perfect précis of the stages of human development: from an infant’s equanimity through the development of character, the recognition of ethics, the tyranny of duty, and the consensus of convention. It is not a progress of growth as much as one of accommodation and diminishment in response to the complications and demands of experience. As in the Tao, so with civility: although they surely have their uses, our goal should be not be the accommodating achievements of duty and politeness, convention and etiquette, but the deeper ones that define a truer way: the soul of civility, and not its costume.

That civility, to say nothing of the soul, is archaic in or day and age, as the lexicographers of Merriam-Webster suggest, is to put it in the same bin with the humanities themselves, construed as outdated by many because they require an apprehension—“an understanding and carefulness of life and beauty”—that has an emergent and informing substance rather than an immediate return. They may be seen as neither efficient nor marketable, but they are sustaining and meaningful nonetheless.

The Tao Te Ching is among my 1,000 books, as is a work called The Geography of the Imagination, by a notable citizen of Lexington, Guy Davenport, who died in 2005. A longtime presence at this city’s University of Kentucky campus, Davenport was one of the great teachers of our time, a one-man renaissance who enriched the minds of both his students and his readers. As Transylvania professor Richard Taylor knows, because he quotes the sentence in the introduction to his own book Elkhorn, Davenport once wrote: “Art is always the replacing of indifference by attention.” And I think we might say something similar of civility: it is a function of the quality of our attention rather than the formalities of our behavior.

Etiquette, after all, is in one way the codifying of indifference; civility, in its venerable sense, a steeping in the humanities, is the shaping of our presence in the world: a way of life. The quality of our attention, of course, is shaped by what we pay attention to. In a book called The Attention Merchants, published a couple of years ago, Tim Wu writes: “As William James observed, we must reflect that, when we reach the end of our days, our life experience will equal what we have paid attention to, whether by choice or default. We are at risk, without quite fully realizing it, of living lives that are less our own than we imagine.”

And William James himself, another author represented among my 1000 Books, wrote this: “Millions of items of the outward order are present to my senses which never properly enter into my experience. Why? Because they have no interest for me. My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind—without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos. Interest alone gives accent and emphasis, light and shade, background and foreground intelligible perspective, in a word. It varies in every creature, but without it the consciousness of every creature would be a gray chaotic indiscriminateness, impossible for us even to conceive.”

“Only those items which I notice shape my mind.” Which means that what we choose to notice may be the most important continuous decision-making we do, whether we are aware of the choices or not. In important ways, a training in the humanities relies on the cultivation of our own interests, and thus civility, in that old sense of the word, is the first bulwark against indiscriminateness.

Yet we live in age of news feeds, of often benign but all-too-often perniciously targeted information in which indiscriminateness is disguised as its opposite, a kind of collectively individualized experience in which we are habituated not to noticing but to consuming. It is not our attention that is served, but rather, our distraction.

There is a new book of essays on this theme—called, appropriately enough, Attention—by the novelist Joshua Cohen. In a review of it published in the Wall Street Journal about six weeks ago, Zachary Fine spoke about the pitfalls of our newsfeed world as he parsed Joshua Cohen’s meaning:

“What does it mean, Mr. Cohen wonders, to live online, in a ‘land’ without a common culture—that’s inimical to a common culture—where facticity is under siege, where identities are worn and shorn and shed like clothing. Images of mass death, reports on the salubrity of butter, sound bites of the swallow’s birdsong: ‘We click away,’ [Cohen writes], ‘but then we return, but then we click away again.’ Distractions, expertly engineered, squeeze our attentions for profit all day, and then we return home tired, fumble through the dark and hunger for our screens again—another distraction in this unending, grim regress.

“To live in America today,” Mr. Cohen writes, “is to sit slackjawed at a helpless recline, stuck between the external forces that seek to disempower and control us, and our own internal drives to preserve, protect, and defend our hearts and minds.”

Space for our hearts and minds—space for both to breathe, and stretch, and grow—is something reading creates. That sense of agency that reading gives us, that we also get from browsing in a bookstore and coming upon something we didn’t know we wanted but that speaks to us with urgency and charm, is something that I’ve sought to get between the covers of my book for the pleasure of readers first, but also for a larger purpose: We live in an age of algorithms, in which all of human experience is subject to rules of engineering efficiency. That’s marvelous, and even liberating, in many ways.

But the most important experiences in life are not efficient. Infancy isn’t efficient, nor is growing up. Education is not efficient, and is less and less education in its true sense the more it pretends to be efficient. Raising children isn’t efficient. Taking care of aging parents isn’t efficient. Falling in love isn’t efficient, and falling out of love is even less so. In fact, thinking is seldom efficient, nor are the revelations we come to about ourselves and the world by living, pondering, and worrying until we learn to be comfortable in our own skin.

Reading of any kind helps us with the living, pondering, and worrying that shapes us, not so much by delivering instructions as by allowing us the space to discover inspirations and develop our intuitions—space in which we can learn to talk to ourselves more thoughtfully than the press of events usually allows. “Becoming is a secret process,” Heraclitus wrote more than 2500 years ago, as noted by Guy Davenport in his book of translations of that ancient philosopher, as Professor Taylor again noted in his book, Elkhorn. It is, in fact, the age of the book which created that space in which our hearts and minds take shape. It was reading that created what we think of now as the inner life, the secret process of becoming ourselves.

Let me explain.

We seldom recognize liberty of attention as a fundamental human achievement—as something that wasn’t always available to be taken for granted. Nor do we appreciate what a remarkable cultural artifact the inner life is; that it is an artifact can be discovered be delving into the history of reading, especially during the first centuries after the first millennium of the common era. Let’s take a dive.

At the Marseilles monastery established by John Cassian in the early fifth century, the founder’s works, based on scripture and the experiences of the Desert Fathers, were read aloud constantly at supper. Such tuning of the ear to the word of God and its echoes was called lectio divina (divine reading); it provided a storehouse of matter for meditation. Four centuries later, as we read in Michel Rouche’s essay in “The Early Middle Ages in the West” in A History of Private Life, the Benedictine rule—adopted by all monasteries throughout the Carolingian Empire in 817—“required each monk to chant or recite all the psalms every week.” Lectio, divine as it was, was still vocal and aural; the inwardness it fostered resounded with oracular echoes.

Yet, Rouche informs us, Saint Benedict himself was instrumental in encouraging private reading, setting aside for it in the monkish regimen “two hours every morning from Easter to the first of November, and three hours in winter.” Still, “Reading was almost always out loud, since in those days the texts had no punctuation and words were not separated.” The solitude of silent reading had yet to be discovered.

Three centuries on, Hugh of St. Victor’s Didascalicon, an early encyclopedia and guide to the art of reading, anticipated the leap from monastic texts (designed for oral, collective recitation) to scholastic works (texts organized for soundless, contemplative, individual study). The springboard for the shift, Ivan Illich asserts in In the Vineyard of the Text, his fascinating study of Hugh’s treatise (and another of the books among my 1000), was a series of technical innovations—improved punctuation, indentation, titles and headings, chapters, indexes—that enabled and encouraged a new treatment of words on a page. As a result, authors were transformed from tellers of tales to creators of texts, auditors were transmuted into silent readers, and thought filled the voice’s vacuum. Apprehension was exchanged for comprehension, inquiry for oracle. All that would grow from the bookish life followed.

“That which we mean today, when, in ordinary conversation, we speak of the ‘self’ or the ‘individual’,” Illich writes, “is one of the great discoveries of the twelfth century. Neither in the Greek nor in the Roman conceptual constellation was there a place into which it could be fitted.” This discovery, too, is at the foundation of the age of the book, for not only does reading, as Illich notes, presuppose private space and the recognition of the right to periods of silence, but the medium of the book creates and shapes a mental space that did not exist in quite the same way before. Within this space is a field for ordering reality according to the reader’s lights and intuitions, a personal reality distinct from, albeit in conversation with, the world outside.

This inward movement of attention is one of the great migrations in the history of the West, through gateways of pages, opening into chambers of reflection, learning, and wonder that might prove independent of the volumes’ contents. Inwardness revealed its own rich territory, of pondering that stretched beyond prayer, and solitude unfolded into the rich tradition we’ve come to know as humanism. The humanities were cultivated in this space that reading created, and civility followed.

The new kind of reading that was fostered by the technical improvements Illich identifies also abetted, eventually, the composition of literary works which in turn conjured new resources—tools for the mining of the imaginative space reading had created. The most magical period of that conjuring occurred in a few decades falling on both sides of the year 1600, when three towering presences in my book—the French essayist, Montaigne, the English playwright Shakespeare, and the Spanish novelist Cervantes shaped in language the modern mind and the culture it would inhabit. That these three were alive and writing at the same time is one of the wonders of history, and coincidence of an especially telling sort. With their works, they expanded literary language into a dimension that would become as essential to our lives as time and space, a dimension in which we could search for meaning, and learn to make it. Through essay, dramatic verse, and novel, this trio engendered and gave shape to what we have come to take for granted as the landscape of contemplation and action, informing not only our conception of human nature, but of human potential—the maturation and significance of our lives—as well.

Indeed, the literary revolution Montaigne, Shakespeare, and Cervantes fomented, one might argue, was every bit as influential in nourishing the historical courses of Enlightenment and democracy as the scientific revolution to which credit generally devolves, and just as dependent upon the development and promulgation of method. The invention of large parts of that literary method, as useful an application of intelligence as its scientific counterpart (and maybe even more so), can be traced back to these three seminal writers. In different ways, each brought to a head the force of vernacular language set free by the decline and fall of the Latin empire, inventing a form that force would evolve on the pages of subsequent generations of writers. With all three, writing was an inquiry rather than a memorial, and even today their works retain a kind of provisionality that interacts with the personal perspective readers bring to it at any given point in time; they are more like organisms made of words than immutable texts—or, dare one say it, like software intuitively responsive to user interaction (reading Montaigne’s On Experience at nineteen is substantively different than reading it at fifty-nine, and you can do your own math on King Lear; Don Quixote’s delusions, it goes without saying, become more sympathetically poignant the older we get). It’s hard to imagine artificial intelligence more revelatory than that embodied in the words of these master artificers.

In real ways Montaigne can be said to have invented the essay, at least as a private chamber on the page which could be decorated with mental furniture—qualms, hesitations, ideas, the flotsam and jetsam of reading—that could then be rearranged to make a habitable space for self and soul. Shakespeare did something similar on the public venue of the stage, turning it into a laboratory of human interaction in which the medium of discovery was a probing, playful language that invoked the contents of hearts and minds and made them visible to audiences (if not always to the characters); the core of his art is the soliloquy, which he fabricated in the same way as Montaigne conjured the essay, creating a space in which a mind could unpack itself while an audience followed the unfolding (that space would prove cavernous and consequently resonant: one can wander within the vaults of Shakespeare’s soliloquies for years, uncovering wonders like an archaeologist of worlds past, present, and to come).

While the singularities of Montaigne and Shakespeare are easy to see and wear a grandeur that is undeniable, Cervantes’s achievement is disguised not only by its comic dress, but by the amorphous being and volubility of the narrative form he created for it: the modern novel, in which a story interrogates itself even as it puts its characters through their paces. Cervantes made fiction itself a tool of inquiry, letting stories intersect, interrupt, and reimagine each other in the lives of his characters (much as they do, really, in the course of our lives). He uncovered a new world for literary endeavor as surely as the seagoing stalwarts of his time explored new continents. If Shakespeare’s legacy is represented by the soliloquy, Cervantes might be seen to have bestowed upon us, through his own work and that of every novelist who became his heir, the colloquy between the inside of our heads and the outside world that the novel exemplifies, and that Don Quixote taught fiction to empower.

In the story of Quixote, a misguided hero besotted by popular romances of chivalry and steadied only by the hands of a capable and long-suffering companion, Sancho Panza, Cervantes manages to depict—in comedy high and low and in episodes alternately satiric, hilarious, and moving—the battle between idealism and realism that is the unresolved, and perhaps unresolvable, conflict of human existence. He also created two of the most memorable characters in all literature. Four centuries after its composition, Don Quixote still has the power to educate and delight us, and those who’ve yet to read it should be prepared to be transported, astonished, amused, and vastly entertained by Quixote’s follies, Sancho’s instinctive resourcefulness, and—most of all—Cervantes’s ingenuity.

William Egginton’s recent life of the author justly calls him “The Man Who Invented Fiction,” and the history of the novel Cervantes’s invention set in motion is one in which imaginative empathy would nobly struggle to understand human nature and the quagmires it finds itself in. Understanding that we parse life and create meaning in it through stories, Cervantes intuited that truth, and most ideals, were malleable, informed by perspective, context, and subjectivity, and that therefore fiction might be in fact an effective form of pragmatism in the face of life’s messiness. If our apprehension of the world around us is a constructed one, always fictive and emergent, rather than imposed and fixed, our shared perplexity is cause for compassion and generosity rather than ridicule and meanness; that’s the lesson Don Quixote teaches us with joy and charity, delivering light and laughter on nearly every page.

Which renders Cervantes’s book never outdated, but particularly timely today, when the reduction of human singularity to economic and biological processes and data-driven convictions threatens the better angels of our nature once again with devilish imprisonments. Alert not only to its own artifice but to its existence in the world as a book, Don Quixote is a story about stories and how they shape our lives—a brilliant feat of narrative magic that illustrates storytelling’s unscientific but unshakable presence at the root of our humanity. On the one hand an elegy for idealism, it is also a celebration of the power of our fictive apprehensions of the world, and the sympathies they foster, to make unidealized life more livable.

“World is crazier and more of it than we think, / Incorrigibly plural,” wrote the poet Louis MacNeice, and our interaction with that craziness and plurality—the colloquy between the inside of our heads and the outside world—begins, like Quixote’s, in the stories we tell ourselves and in the language we have available to tell them.

If civility requires a common language shared with others, it nonetheless starts in how we talk to ourselves, in that ongoing conversation we have within our heads, and which reading is the best way of nourishing. For books offer us not just texts, but contexts. And as the technological timeline moves more and more rapidly from the age of the book to the age of the screen, the skill of grasping and holding contexts is ever more important. Critical questions are left unexplored, or their consequences are ill-considered, if data alone defines our choices or, worse yet, determines our destiny.

Search, for instance, is a word, and a pursuit, that has lost in luster what it has gained in power in our digital age. Where it once meant adventure, or becoming, or a quest for meaning, it has been reduced to the return of snippets of information, ecommerce promotions, targeted ads, and the false precisions of data’s limited, if powerful, parsing of experience. As useful as it is, we don’t want to run our lives by GPS, where we always know what the next step is, but don’t have a wider sense of where we are and where we might be going. It saves us from the fear of getting lost by sacrificing our freedom to learn how to find our way.

Any structuring of experience that is slave to an algorithm, that keeps us from finding paths that might illuminate our past and surprise our future, does so by making the story of our present more convenient and efficient. But it’s unlikely to be the story that, on reflection, we want our lives to tell. In a news feed, what happens next soon becomes irrelevant, because it will disappear as soon as something else is served in its place. Nothing matters much.

Stories that matter are hard to tell, but the only ones worth living. To tell them well, to live them well, we need the language in our heads to be rich enough to support all the joys and disappointments, the sorrows and the blessings, that life sends our way.

The more nuanced and flexible that language, the firmer its grasp on our experience, and the better we’ll be able to share our stories, and to understand those told us in return. Thus giving the archaic meaning of civility—a training in the humanities—a fresher one, one that is not merely formal but substantive, compassionate, and maybe even magnanimous. There is no public civility without a private one beneath it.

In “Aspohdel, That Greeny Flower,” William Carlos Williams said all of this much more eloquently, and succinctly: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.” And what is it that is found there? Not certainties, but conversing truths: the still small voice of a writer talking to a reader, and a reader talking to herself.

Do you know a book by Claudia Rankine called Citizen? It was published in 2014 and won the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry (in a sign of the book’s multivalent singularity, it was also a finalist in the Criticism category). Rankine’s remarkable book is about being a citizen in an uncivil union in which one’s figure in the world is alternatively ominous and invisible. It also has the distinction—and this is why it is among my 1000—of creating a private voice—an interior one—to amplify and make resonant the most difficult public themes.

“Yes, and this is how you are a citizen,” we read as we approach the end of this book about race, identity, language, and memory: “Come on. Let it go. Move on.” The phrases echo others sounded on earlier pages in their urging that the consciousness at work—the “you” being addressed—evade engagement with racial hostility, disregard the insults of insensitive slights, swallow pride in the face of prejudice ignorant or intentional: “Then the voice in your head silently tells you to take your foot off your throat because just getting along shouldn’t be an ambition.”

While, given such deadly serious subject matter, the book’s subtitle—“An American Lyric”—might seem ironic, it holds the key to Rankine’s most telling achievement, for the composed space of reflection and repose that is the domain of lyric poetry provides a magnifying frame for everything Citizen encompasses. It is clearly drawn in the book’s initial paragraph: “When you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices, you let yourself linger in a past stacked among your pillows…. [The moon’s] dark light dims in degrees depending on the density of clouds and you fall back into that which gets reconstructed as metaphor.” It is exactly because Rankine is a lyric poet of such extraordinary gifts that she cannot comply with the demands her citizenship demands: “Come on. Let it go. Move on.” In the pages of Citizen, she holds fast to what’s she seen, brings close what others have felt and suffered, breathes language into the deadened air of grief, forcing herself—and her readers—to scrutinize the pain that racism provokes, and to stand still and ponder its cumulative injury and sorrow.

Reading Citizen, or Don Quixote, or the soliloquies of Shakespeare, or the essays of Montaigne or Guy Davenport, nourishes our inner life, alerting us, through the words of others, to the vocabulary and grammar we need to make sense of our own lives.

This faith in reading’s power, and the learning and imagination it nourishes, is something I’ve been lucky enough to take for granted as both fact and freedom; it’s something I fear may be forgotten in the great amnesia of our in-the-moment newsfeeds and algorithmically defined identities, which hide from our view the complexity of feelings and ideas that books demand we quietly, and determinedly, engage.

To get lost in a story, or even a study, is inherently to acknowledge the voice of another, to broaden one’s perspective beyond the confines of one’s own understanding. It makes us better speakers, and better listeners. A good book is the opposite of a selfie; the right book at the right time can expand our lives in the way love does, making us more thoughtful, more generous, more brave, more alert to the world’s wonders and more pained by its inequities, better speakers and better listeners, more wise, more kind.

A better education in civility is hard to imagine.

Thank you for listening.